Why I Consider Cagney & Lacey the Best Show on TV

TV Guide January 16, 1988

I consider Cagney & Lacey the best show on television. Launched as a CBS TV-movie in 1981 and as a series in 1982, it honors women's friendships and represents a radical departure from the myth that women can't get along.

Before that, women on TV tended to be tokens in a man's world, or else rivals for a man's affections. In the few instances when women were permitted to be friends (e.g. Lucy Ricardo and Ethel Mertz), the relationship was comedic, and often catty. And the women weren't working together. Christine Cagney and Mary Beth Lacey, two New York City police officers, are work buddies in a way that only male characters have been in the past.

More recently, Kate & Allie has come along, another well-written CBS show based on friendship between women. But here the premise is: here we are together, without men. Kate McArdie and Allie Lowell are thus defined as victims. Allie's constantly saying rotten things about her ex-husband-as if you can't be friends with a former spouse.

Cagney and Lacey's friendship is not defined in terms of men. Lacey happens to have a wonderfully complex and involving marriage, while Cagney is a career-driven woman with no particular desire to settle down. They're friends because they admire each other's honest and competence, and because they can rely on each other in a dangerous job that they both love.

The quality of their friendship has humanized cop shows. In fact, along with NBC's Hill Street Blues, Cagney & Lacey has brought a human resonance to TV police work that renders the simple good guy/bad guy cop shows of the past hopelessly obsolete.

Hill Street Blues, an excellent show, was innovative structurally, handling multiple plots in a real way. But to me, Cagney & Lacey has more depth. The characters are so fully realized that you find yourself worrying about them as people. In one episode, Chris Cagney's father, an alcoholic, dies after a fall in his apartment. Cagney's desperate attempts to revive him are grippingly real. Later, at the wake in Flannery's bar, she toasts his memory with repeated libations, and the viewer has a nagging worry that alcohol might become a problem for her, too.

In a recent episode, Cagney is raped by a man on a first date. Her cascading feelings of bewilderment, shock, shame and fury are handled sensitively. Equally well portrayed is the lack of understanding by some of her friends. Cagney's boy friend, David Keeler (Stephen Macht), for instance, later tells her: "All I care about is you, Chris. Thank God, you're not hurt." She looks at him in disbelief: "I was raped. I am hurt."

It's significant that this date rape, as it's called, happens to one of the show's principals, indeed to a strong, feisty, resourceful woman-rather than to a character the audience doesn't care about. If it can happen to Cagney, viewers realize, it can happen to anybody.

The legal aspects are well-drawn, too. Because her assailant is a clean-cut company president, and because she has no bruises to show, it seems doubtful that she can win her case against him. But the fact that Cagney-a major role model for women-does press charges should encourage other women to do so.

I particularly like the fact that the scripts usually don't take the easy way out. Cagney is not suddenly all better; the emotional issue of Lacey's abortion was never entirely resolved. Some scripts are so strong that they might actually change people's attitudes. One story line, for instance, has Cagney in a love affair with a disabled man. Through this we see that sexual attractiveness is not negated by a wheelchair. But the story doesn't end there. In order to catch a criminal, Cagney puts herself in a wheelchair and masquerades as a disabled person. Suddenly she finds people looking at her differently-looking right through her-and treating her as if she were mentally, not just physically, impaired. Anyone seeing that episode can't help rethinking his/her attitudes towards the disabled.

The supporting characters are also well-delineated, particularly Lacey's husband, Harvey, played by John Karlen. Harvey's a wonderful man, a blue-collar worker who's not an Archie Bunker. He's married to a strong woman in a nontraditional role, and they have a good marriage. Bunker would never want his wife, Edith, to go out and get a job, much less a "man's" job; but statistically Harvey's attitude is closer to reality. Blue-collar men do tend to be more supportive of economic equality for women. Granted, they're not leaping forward to do the dishes, but they're more used to needing two incomes to get by.

I'm not saying that the program couldn't be improved. I wish, for instance, that the writers had expanded Cagney and Lacey's alliance with the black detective, Marcus Petrie (played by Carl Lumbly). In the original TV-movie, more was made of this, and properly, because it's real. Outsiders do band together, and women and blacks have been relative outsiders in the law-enforcement establishment. Now Lumbly has been replaced by a black woman, Merry Clayton, as the strong-willed Det. Verna Dee Jordan. Whether she proves an ally or an antagonist to officers Cagney and Lacey remains to be seen.

And socially, it would be nice if the show were a bit less hermetically sealed. There's Cagney and Lacey and their families and their jobs and that's it. But in real like there are frequently networks of women. Christine and Mary Beth don't seem to have other friends.

Also, since the show is filmed in California, one misses some of the ethnic diversity that one might find, for instance, in a show shot entirely in New York. Generic shots of a clogged highway and the sign "Entering Queens" are not enough to convey a full sense of authenticity.

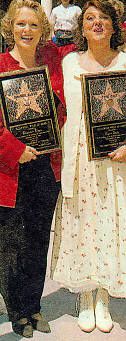

The most authentic touches are found in the wonderfully strong acting of Sharon Gless, as Cagney, and Tyne Daly, as Lacey. The characters are so convincing that one can imaging them growing and changing, like real people. It's this human accuracy that makes the show attractive to women, who tend not to care for the usual cop shows.

In fact, one hears that women identify strongly with both the very married Lacey and the very single Cagney. After all, even though few women are police detectives, most women have demanding jobs, whether inside or outside the home, and they rely for support on close women friends. Cagney & Lacey is one of those rare shows that reflect the reality of women's lives. If this turns out to be its last season (the ratings the show receive in its new Tuesday night time slot will determine its fate), it will be missed.

Back to start of Cagney and Lacey section

My Index Page

|