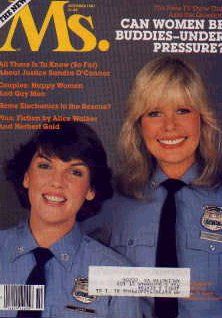

Cagney and Lacey

Can women be buddies-under pressure? And have laughs and adventures besides? Television execs said no-but here's what happened. (Ms, Oct. 1981)

Stealthily the police officers pad across the city roof and circle the skylight. They peer through the panes of glass to the lot below where a group of people in surgical masks are sitting at a table measuring white powder into a mixing bowl, then stirring it with wooden spoons. The officers look at each other and nod, the signal to lift the skylight and point their guns inside. "Freeze!" they shout. "Police!"

The scene seems familiar: variations on it have been played many times before in many movies before, but never quite like the one being played here and now in CBS's extraordinary TV Movie of the Week, "Cagney and Lacey" which will air in October. For here and now New York's finest, those brave little men in blue are in fact brave little women in blue. This is a movie about them- their relationships to each other, to their work, and to their male colleagues on the force.

Chris Cagney and Mary Beth Lacey are two women cops in the N.Y.P.D. Neither is a precinct superwoman. Cagney, who is single, is a headstrong rebel too impatient to follow orders or observe protocol. Lacey, the married one, is her opposite-cautious, nurturing, the peacemaker trying to preserve a problematic marriage, a woman by nature too conservative to deviate from the rules. Together there's a team responsible for each other's well-being and life, and thanks to an outstanding record they are promoted out of uniform into plainclothes work. Being female, they are immediately shunted onto the john detail, which not only requires them to "disguise" (read humiliate) themselves as prostitutes and busy themselves with "victimless crimes" but also distances them even further from more important and pressing cases at hand. One such case involves finding the brutal killer of a Hasidic diamond merchant, and although Cagney and Lacey's superiors in the precinct are not disposed to assign them this investigation, Cagney especially wants a crack at it.

If "Cagney and Lacey" seems the perfect and even obvious answer to those male-dominated buddy-buddy movies such as "Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid" and "Scarecrow" that proliferated back in the early 1970s it is an answer that should have come earlier. Had circumstances been different, it would have, for this movie has taken six years to reach the screen and might never have done so had it not been for the resourcefulness of its guiding light, executive producer Barney Rosenzweig, and the inspiration of his team of writers, Barbara Avedon and Barbara Corday who, in different degrees and capacities, developed both the project and Mr. Rosenzweig's feminist consciousness.

"Let me go back to 1975", Barney Rosenzweig recently recalled. "I had known the writing team of Barbara Avedon and Barbara Corday professionally for about six or seven months and I had just begun to see Barbara Corday socially (they are now married). They were both feminists. I, on the other hand, didn't know an awful lot about feminism and so decided it was important to have my consciousness raised. I listened and I read a lot, and one of the things that struck me was the fact that never in the history of Hollywood films had two women had a relationship like Robert Redford and Paul Newman in "Butch Cassidy", like Elliott Gould and Donald Sutherland in M*A*S*H. The Hollywood establishment had totally refused women those friendships, the closest thing being perhaps Joan Crawford and Eve Arden in "Mildred Pierce" the tough lady boss and her wisecracking sidekick. So I went to my friend Ed Feldman, who was then head of Filmways Productions and I said, 'I want to do a picture where we turn around a conventional genre piece like "Freebie and the Bean" with its traditional male situations and make it into the first real hit feminist film.' Ed loved the idea and gave me seed money to hire writers. I suggested the team of Avedon and Corday."

Barney Rosenzweig and the two Barbaras, as he came to refer to them, began a series of conversations about the project. "I told them they could say anything they wanted to in the body of the piece, but that the only way this was going to get made was if it as funny and entertaining."

At this point, the two Barbaras flew to New York to do research with the N.Y.P.D. Barbara Avedon, whose impressive credits include writing for TVs "Father Knows Best" and also the "Mr. Magoo" cartoons, for which she won an Oscar, recalls "We spent about ten days traveling around in cop cars and going to precincts all over town. We visited the Police Academy and we talked to fifteen to twenty women. It was fascinating. The women cops we met were first and foremost cops. Unlike Angie Dickinson in "Policewoman" who'd powder her nose before she went out to make a bust, these women took themselves seriously as police officers."

Back in Los Angeles, the two Barbaras fashioned a first draft of the script. Originally entitled "Freeze" it was much spoofier than the script that exists today, and it employed high physical comedy in telling the tongue-in-cheek story of how Cagney and Lacey deduce the existence of The Godmother, the secret head of the Mafia and the great female mind behind a brothel where women are the patrons, men the prostitutes. "Don't forget it was 1975 and we were aiming for a situation that would show women as equals in a close friendship and a movie that was just as silly, just as funny, and that employ just as many car crashes as the male buddy movies did," explains Barbara Corday.

Originally the project looked as though it would sail quickly into production "But what we did not anticipate," Barney Rosenzweig comments "was the fact that, as subtle as we were, there were things in the script that at the time either didn't appeal to, or were offensive to, the male-dominated Hollywood establishment. Remember, every studio was then run by a man, and our women cops were just like two fellows, they even used four-letter words, and apparently that rubbed a lot of executives the wrong way. 'These cops,' the executives complained 'aren't soft enough, aren't feminine enough', all those cliches. But Sherry Lansing, who was at the time an assistant to Danny Meinck, then head of MGM, loved the script and was chasing him up and own the streets to get him to do the picture. And because Dan got tired of Sherry nagging him, he finally made a sort of left-handed commitment to the project, saying that if we could supply a certain type of casting and make it for a certain price, he'd do it."

The kind of casting that appealed to Dan Melnick was pairing such stars as Raquel Welch and Ann-Margret as Cagney and Lacey. In the trade it's often called exploitative casting. However, sometimes exploitative casting presents a Catch-22 situation all its own. "Danny Melnick was going to make the picture if we could get Raquel Welch and Ann-Margret and bring it in for under $1.6 million, but unfortunately the price and the casting precluded each other. Frankly, for $1.6 million, you couldn't make that picture with my aunt and uncle, let alone with Welch and Ann-Margret.," Barney Rosenzweig observes. And so "Cagney and Lacey" began sliding imperceptibly into the never-never land of underdeveloped and unfortunately developed development deals.

Still, "Cagney and Lacey" remained a favorite project, close to everyone's heart. And about a year and a half ago, Rosenzweig decided to pluck it from never-never land, dust it off, and try again.

"I'd say it was ninety-eight percent Barney's perseverance that got this movie made,"Barbara Corday says. "Most people would say to us 'Please! On to other things! Why are you guys still messing around with that script? But if there's something you really love or care about, why would you give it up? You don't have to spend twenty-four hours a day on it, but whenever there's a shot at it, you take the shot. This is especially true since executives turn over so frequently at movie and television companies that every year or two you can bring back projects they've already turned down.

This time around, Barney Rosenzweig decided to take "Cagney and Lacey" to the networks rather than to the movie studios. He had a track record in TV, having since 1975 line-produced 12 of the original "Charlie's Angels" shows and produced such Movies of the Week as "Angel on My Shoulder" and such mini-series as the blockbuster "East of Eden". Furthermore, television has in the past few years been dealing with the kind of relevant "theme" material that studios, anxious for surefire box-office hits, are reluctant to gamble on. But because both Barney and the two Barbaras felt that the feminist perceptions and the material itself, written back in 1975, might now appear dated, they decided to rework it. Moreover, since the kind of extravagances and unreality suitable for film are often less effective on the homescreen, they chose to throw out their Godmother idea and build in a strong, believable plot with a realistic crime story for Cagney and Lacey to solve. The two Barbaras constructed a new story around the murder of the diamond merchant, and developed an interesting subplot about prostitutes, but because Barbara Corday had in the interim made a significant career change and was now working as vice-president of comedy development at ABC, the task of writing the new script fell to Barbara Avedon alone. Meanwhile Barney Rosenzweig put together key scenes from the screenplay and presented them first as a proposal for a television series and then, when that failed, to CBS for a movie for television. The CBS executives immediately loved the idea. At that point Richard M. Rosenbloom, Filmways staff producer and president of Filmways Productions, Inc., came into-and onto- the picture. As the movie's line producer, working in conjunction with Barney Rosenzweig and in charge of the day-to-day physical problems of the production, it was among his initial responsibilities to convince the Filmways executives that the project could be made in Toronto for $1.85 million, and then to convince CBS that although "Cagney and Lacey" would be filmed in Toronto, it would ultimately look as it was shot in New York (Rosenbloom had, by the way, been in charge of accomplishing similar feats with other TV movies such as "Hustling" and "Street Killing". Both filmed elsewhere, they rated a surprisingly authentic sense of New York City). That done, the CBS executives gave the project a go-ahead suggesting, however, two young stars to play Cagney and Lacey. "You don't understand, " Rosenzweig admonished "These policewomen must be mature women. one has a family and kids, the other is a committed career officer. What separates the project from Charlie's Angels is that Cagney and Lacey are women, they're not girls and they're certainly not objects."

He won his point, and he and CBS have been in sync ever since. Eventually Loretta Swit, the star of M*A*S*H and Tyne Daly, the intense actress who played a female cop opposite Clint Eastwood in "The Enforcer" a few years back, agreed to play Cagney and Lacey-casting that adds a touch of class to the project. Moreover, the film's director, Ted Post, is a man of experience as an action director with credits such as "Hang 'em High," "Go Tell the Spartans" and "Beneath the Planet of the Apes." And just to make sure that there was no question about, or misinterpretation of the script, Rosenzweig discussed the movie line by line with Post and spent more time on the set than on that of any other picture he has produced.

But the striking thing about the history of "Cagney and Lacey" is that, despite the struggles and compromises and changes, Barney Rosenzweig's persistence has paid off-a rare Hollywood happy ending. The script is exciting, funny, and touching. "When I first began to read it, I was going to say, 'No, thank you.' It was the farthest thing from my mind to play a policewoman," Loretta Swit admits. "I was afraid that I wouldn't understand a person who wears a gun as part of a job. It seemed like a hundred-and-eighty-degree turn for me because I'm (a) a pacifist (b) for gun control and (c) for peace-I've worked the last nine years in a show that endorses peace. So I had a lot of doubts. But the script impressed me. it was a good story with a lot to say about women and sexism. However, before I committed myself to it, I did a few weeks of research with a policewoman. Every day I went out in a patrol car. I learned how to shoot and even became a marksman. By the end of my research I was very excited about doing the picture. By now I love this character, Chris Cagney. She's a heroine. She's brave, bright, and ambitious, and I think it's important to see what this kind of woman can do and also what this kind of woman is up against."

Swit also remarks about assuming the role: "A funny thing happens when you put on that police uniform. You feel capable, protective, and you begin to watch out for other people."

The sentiment is seconded by her costar Tyne Daly, who adds "The weight of the gun, the Mace and all that equipment around your hips changes your walk and your focus. You look outward onto the street. You're sharp, you're aware of everything that's happening around you. You feel protective."

It's hard to assess just how all this will do in the ratings, but given the talent and the material, great expectations are in order. For the script is alternately lighthearted and dead-earnest, with points that hit home with clarity. For instance, early on we are introduced to Chris Cagney. She is climbing out of bed and into uniform while an anonymous lover sighs "You were terrific" and waits for similar confirmation from her. But all she offers is a crack "New York's finest." While he is begging her to take the day off and spend it with him, she is gearing up for the work ahead and is already millions of emotional miles away form him. "I'll call you," she says absent-mindedly before disappearing out the door.

Later in the movie Mary Beth Lacey and her husband fight. As they argue, she dissolves into tears and he stands buy, muttering 'Hey, honey okay. I'm sorry." But Lacey is frustrated not only by the fight but by her tears that suggest helplessness rather than the more appropriate fury. "I'm not sad," she screams. "I'm mad...and I'm madder because I'm crying when I'm mad. I don't want to cry when I'm mad. I wanna..." And she takes her sneakers and flings them across the room as if to punctuate her frustration.

It's scenes like this that set "Cagney and Lacey" apart. And so, if the story of its long and painful path to production is a typical one, the movie itself is not typical at all. For it has a particular vision-one set apart by dint of its wit and its political and emotional resonance.

Still, watching "Cagney and Lacey" it is virtually impossible not to think of its potential as a weekly series. For here's a rare TV movie that not only sports such surefire ingredients as crime, cops and a pair of great buddies, but also maintains its distinctive focus on two highly individualistic, courageous and thoroughly independent women-women we'd like to get to know better, and women who are worth visiting with again and again.

Back to start of Cagney and Lacey section

My Index Page

|