An Australian Film Reader-"Peter Weir's Hauntingly Beautiful Film Makes The Film World Sit Up

From a book edited by Albert Moran and Tom O'Regan

With Picnic at Hanging Rock the Australian film has truly entered into the field of open and equal international comparisons, needing no allowances for inexperience, nor special consideration for having been home produced. Directed by Peter Weir, it is a superb and beautiful film, virtually perfect in its balance and delicacy, handling its incidents with such skill and sensitivity as to leave one almost breathless.

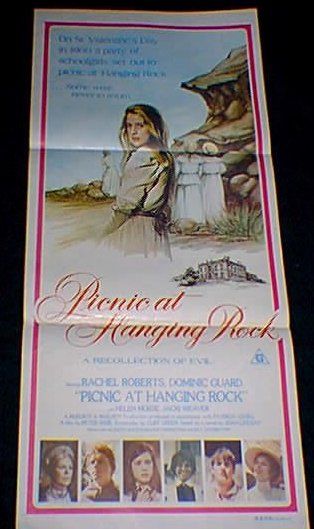

Joan Lindsay's book of the same title tells the story of a party of schoolgirls, from a select academy for young ladies, who go on a picnic on St.. Valentine's Day, 1900. Several of them disappear, and despite frantic searching, are never seen again. Nobody knows what happened; no trace of them is ever found. That is, with the exception of one girl who remembers nothing of what took place. The disappearances carry further consequences, and lead to the end of the Appleyard Academy.

As his previous film, The Cars That Ate Paris, showed, Weir has a talent for conveying an atmosphere of the sinister; this now comes to full flower as a hot, languid summer afternoon, cicadas crying and young girls in long white summer frocks drowsing, gradually deepens into a mystery.

As the mysterious events unfold, a sense of some unnameable horror, some unlocatable threat develops also-the Hanging Rock looms over the action exuding a dark miasma which is only intensified by the brightness of the sunlight and the idyllic bush scenery. The pent--up sexuality of the girls manifesting itself in excitement about St. Valentines Day, the normal intense friendships, and affection for a pretty French teacher, turns to hysteria which in a quite frightening climax bursts out when a group of girls at gym practice suddenly turn on the sole survivor of the disappearance and almost seem to be about to tear her apart as they demand an explanation. And finally, the headmistress drives one of the girls to suicide, and sits, like Miss Haversham, in the ruins of her hopes.

The casting and the acting fit the mood of the film exactly. Rachel Roberts as Mrs. Appleyard, the proprietor and headmistress, gives a precise portrayal of narrowness and cruelty in the high Victorian moralistic manner. It is difficult to single out any of the actresses playing the girls for special comment if only because the school actually seems to exist; it is as if these girls really did live together in that vile institution, a boarding school, and in fact complemented each other as they do in the film. Bruce Smeaton's score contributes greatly to the accumulation of the tension and sense of the mysterious, as does the misty clarity of the photography.

It is rarely that a comparison of style between the infant Australian film industry and a foreign film is possible, but it is no detraction of Weir's film to say that it is in many ways reminiscent of the films of the Swedish director Bo Widerberg, though in Weir there is the extra dimension of horror.

The Cars That Ate Paris was well received by the critics who saw it at the Cannes Film Festival in 1974, and obtained much favourable comment. Picnic at Hanging Rock, which is easily the most mature and skillful Australian feature film yet, will, I hope, be at Cannes next year. It would have a very good chance of taking one of the major awards. And it will, thank goodness, demonstrate that Australian film-makers are capable of much more than the coarse and vulgar rubbish like Barry McKenzie and Alvin Purple.

That Australian audiences too can recognize real quality in an Australian made film is shown by the success that the film has so far had in Adelaide, where it is still packing them in it its twelfth week. Let us hope that it has an even greater success in Sydney and Melbourne; certainly there is no better film showing in either city.

National Times, 20 October, 1975.

Back to start Picnic at Hanging Rock section

My Index Page

|