An Australian Film Reader General: The Aussie Picture Show (excerpts)

From a book edited by Albert Moran and Tom O'Regan

The first product of the 'New Australian Cinema' to meet the ultimate commercial challenge of a screening in my local Odeon was Peter Weir's 1973 oddity, The Cars That Ate Paris. ...I hated it!...

I still do, I'm afraid. Nothing about its better known successors, Picnic at Hanging Rock and The Last Wave, has disposed me any more favourably towards its director or the movie itself. What might have been excused in The Cars That Ate Paris as first effort confusions or unavoidable products of a nutty story...have turned out to be basic in Weir's cinema. Though he has proved to be a skilful creator of atmosphere, he has also been much too willing to sacrifice narrative coherence and characterization to a taste for flamboyant effects and heavy symbols.

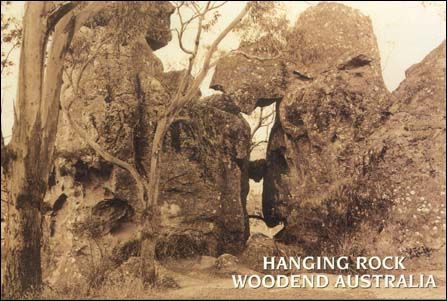

Take the best known of his films, Picnic at Hanging Rock. For a while it works perfectly. The movie's luminous photography and plaintive music, its gently paced opening narrative, the carefully composed images within which its ill-fated party of young women are captured like so many figures in a painting, all these combine to suggest the precariousness of this apparent order, its dependence on repression and collapsing authority. Just as the rock looms over the picnickers, so some indefinable doom hangs over their world.

To climax this elegantly allusive section of the film, Weir gives us one of his best moments. High on the rock Miranda and her followers rest among the boulders, the remainder of their party tiny figures far below them. Then, for no particular reason, three set off to climb yet higher, leaving the fourth, the tubby odd-girl-out, hysterically screaming after them. As they disappear through a gap in the rocks, one behind the other, Weir contrives an extraordinary image. He shows us the girls from behind and in slow motion. We cannot see their faces; only their eerily moving hair and floating white dresses mark them out from the surrounding walls of stone. The long len's flattened perspective makes them look almost as if they were part of the rock itself. They seem to disappear into it, and we are left with a disturbingly unspecific sense of unease.

After that, though, it's downhill all the way. Rachel Roberts, the headmistress, is encouraged to look increasingly witchlike in her dark dresses and shadowy room. Dominic Guard, the young English gentleman obsessed with the mystery, encounters symbolic swans at the foot of his bed, and-of all the improbably twists of melodrama-Sarah, the persecuted orphan, turns out to be sister to the Australian groom down the road. No film, however stylish, can be forgiven those sort of overheated indulgences. If Weir really is as some have described him, the most promising of Australian directors, then the future doesn't look too bright.

Back to start Picnic at Hanging Rock section

My Index Page

| |