The Trials of TV Acting: The Triumph of Sharon Gless

Commonweal,January 11, 1991

"I'm not an actor-I'm a movie star!" That's the wonderful line croaked by Peter O'Toole's character in My Favorite Year, when he discovers that the skit he is supposed to perform on an early fifties TV show is going to be done live, and instantly seen in millions of homes. What makes the line so funny is not just that it invokes the old-and by now largely pointless-snobbism of "the thaytah" about the movie, but that it does so in the context of TV; because if there is any dramatic medium that seems to render the concept of acting as an art almost completely irrelevant, surely it is the Tube.

Let's admit it. In TV, as Robert Frost earlier observed of walls, something there is that does not like an actor. Wonderfully effective

TV actors, like James Garner, David Janssen, and Tom Selleck, have consistently failed to carry their special power over from the small to the large screen, and this cannot be blamed on "bad scripts." Of the few who have made the crossover-Clint Eastwood, say, and Sally Field-it has to be said that the films they make are largely, and cleverly, tailored to the distinctive one-dimensionality they first carved out on the Tube. Dirty Harry and all of Clint's other avatars are all first cousins of the tight-lipped, whispering Rowdy Yates of "Rawhide," And as for all those spunky, naive but goodhearted gals (sure the word is sexist-so are the movies) portrayed by Field, come on: Sister Bertrille in jeans is still Sister Bertrille.

No. If you check out any of the TV nostalgia or trivia-quiz books that seem to be always flooding the market, you notice something curious. The faces with instant recognition-quotient, the faces by which we mark our fifty-year love affair with the Tube, are generally not the faces of actors at all, but the faces of clowns (Milton Berle through Lucy to Candice Bergen), prophets (John Cameron Swayze through Cronkite to Peter Jennings), "real people" (Joe McCarthy to the sad people on "America's Funniest Home Videos"), or caricatures (Howdy Doody through Big Bird to the Simpsons). Damn few actors-who, whatever theory of drama you were force-fed in sophomore year-ought to be clowns and prophets and caricatures, all at the same time.

Does this mean that TV is, as its detractors like to say, a mere commodity, inimical to the finer articulations of drama? That the Tube reduces the actor's craft to nothing more than a harmonic in the brainless carrier-wave of the cathode ray? (I remember-I swear-as a kid seeing Lee J. Cobb perform the last soliloquy of King Lear on "The Dean Martin Show" right between a troupe of Russian acrobats and Dean's closing, sloshed medley at the piano.)

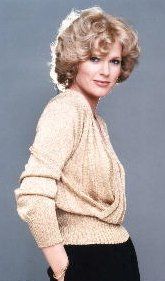

Again, no; it means that we all ought to celebrate Sharon Gless and her new series, "The Trials of Rosie O'Neill."

The very bright Katrine Ames has already highlighted "Rosie O'Neill" in Newsweek (November 5), so the show is probably assured of survival for at least its first season. This is good news because the show's producer, Barry Rosenzweig, who also guided "Cagney and Lacey" (Gless played Christine Cagney) is one of the few people out there who seems capable of dealing with "controversial" subjects and dealing with them from a stance of moral maturity; a Norman Lear with wit. It's even better news because watching Gless work at her craft week after week gives the same intense pleasure as watching anybody really good do what they do (Paula Abdul dancing, John Sununu prevaricating), and also because Gless-I'm serious about this-is virtually defining what TV acting, as high art, is all about.

The premise is almost preemptively ho-hum; Rosie O'Neill (Gless) is a forty-three-year-old, recently divorced woman with a law degree trying to work out her sense of pain and loss by working the Public Defender side of the street in Los Angeles. Oh, yeah; she also comes from this very well-heeled family, and so is regarded as something of your white liberal twit by most of the other studiously ethnic lawyers in her office. One can almost hear, as if it were Fibber McGee's mythic closet, the cliche's about to start tumbling.

But they don't. Rosenzweig is a good and smart producer and hires good and smart screenwriters. And Gless-who has a face and a tone of voice that are damn near a working definition of integrity-seems capable of making almost any line sound like human speech uttered by a human person.

That is no small accomplishment for any actor, but the fascinating thing is that Gless does it on and for TV. On the stage you have to project; any emotion you convey has to be seen by the people in the back row, or otherwise you haven't earned your pay. On the big screen you have to reflect; from an actor's perspective, the special quality of film is that it puts everybody in the front row, so that what might work on stage has to be carefully toned down to the gigantic intimacy of the close-up. Think about the last shot of Godfather II: Al Pacino with the thousand-yard stare and no dialogue and no movement, and if that is not "great acting," then we might as well trash the concept altogether.

But what about TV? And Sharon Gless? Well, every episode of "Rosie O'Neill" begins with Rosie talking in her shrink's office about what has traumatized her that week; bitterness over the divorce, memories of her father, problems dating younger men, etc. And as the camera circles around her-like a predator?-Rosie simultaneously reveals her neurotic pain and bravely, failingly, strives to maintain an ironic distance from it, as if she is, after all, in control. If you're ever been on the couch yourself, you know how common and how desperately important this kind of performance is to sustain. But for Gless to mime it so brilliantly and so regularly is nothing less than an actor's tour de force.

Those openings are, of course, crucial to the political point of Rosie O'Neill;, as a Public Defender Rosie is frequently in the position of defending the indefensible, for the sake of the Law; the Law of nations or the Law of human self-consciousness, which demands that even the most monstrous within ourselves be allowed its voice, since to deny or repress that voice is to deny and repress our full humanity. The pain we feel in defending the "obviously" guilty is like the pain we feel in gazing into our most arid desert places. But it's a pain that has to be endured, if we are ever to be whole.

This is really the special quality Janssen and Selleck and, at her best, Mary Tyler Moore, brought to the business of TV acting; realizing that the great TV actor neither projects nor reflects, but-because of the almost erotic intimacy of the Tube-simply allows his/her vulnerability to emerge under the gaze of the small-screen camera. What makes Gless special is that she seems fully aware of what she's doing, fully aware that her little twitches and voice cracks and misdirected eye-movements are the building-blocks of a new version of one of the most venerable arts.

The real Cagney-James-once said to a nervous young Pamela Tiffin on the set of his last starring movie, One, Two, Three, something that is virtually a compendium of, and a blessing upon, the actor's art, "Don't be afraid," he told her, "Just walk on to the set, plant your feet, and tell the truth." I like to think that, somewhere, that great and gifted man is smiling and nodding at the work of the tough and witty woman who was once his namesake.

Back to start of Sharon Gless section

My Index Page

|