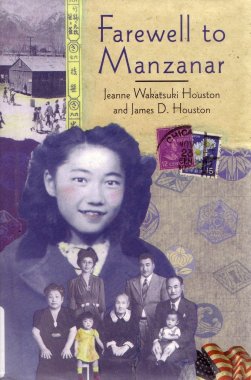

Farewell to Manzanar

This is a more personal look at internment rather than many of the other books which examine the internment as a historical event. It's written by a member of one of the first families to arrive at Manzanar.

She starts off recounting how her father was a fishermen and that opened him up to being one of the first arrested in the crackdown on Japanese-Americans just after Pearl Harbor. The government used the idea that since the men were fishermen than they are potentially in contact with Japanese enemy vessels and therefore needed to be removed from the entire area as quickly as possible.

She recounts how her father burned their Japanese flag and various papers. This is something that many of the Japanese-Americans did, destroying any of their possessions that tied them in closely to Japan, hoping that it would help them avoid trouble with the legal authorities. It didn't. All that happened was that they lost a lot of their culture for nothing.

She didn't see her father for a year after the FBI showed up and took him. Then comes a series of moves for what remains of her family and growing hostility at school towards her. Before long she's headed to Manzanar internment camp.

She describes the conditions in the camp and there were not exactly what one would call wonderful. The camp wasn't ready for them when they moved in, many things didn't work and the conditions for food preparation would have gotten any restaurant shut down. Food spoilage was a major problem with the sickness that ensued from it.

There was virtually no privacy, bitter cold and major wind and sand problems. There was also a major cultural problem that arose. Japanese families were extended families, several generations living together. It resulted in a close-knit family relationship and one that worked quite well. Once in the camps, though, that family relationship began to fall apart. Many of the men were not even in the same camp, having been arrested earlier and taken elsewhere. The elderly at times were too old to do all the walking required to get to mess halls, etc, and so the families did not always eat together. Thus, not only were the Japanese-Americans suffering economically, but even their culture was under attack.

Their father returned after nine months in custody. She then goes into her father's history. He was changed by his experience, though, and when he returned to the camp his behavior was different and he developed a serious drinking problem. In addition, some of the people in the camp thought he was a collaborator.

She then goes into the history of the Manzanar "riot." Fred Tayama, a leader in the Japanese American Citizen's League and someone who was too close to the camp's administration was beaten by six men. He wasn't able to identify the men but the next day three were arrested anyone, one of them a cook who had been complaining about food being stolen by the white chief steward.

The leader of the rioters was Joe Kurihara who was in the U.S. Army in WWI but was still interned despite his already having served his adopted country. Speeches were made saying the reason the cook was arrested was to cover up the food theft. One group went to find Tayama and finish beating him up, the other group headed to the police station to free the cook.

The second group was met by MPs who fired tear gas and then, as the men were dodging the tear gas, they opened fire. The result was one dead then, one died a few days later and ten others were injured. The riot ended.

Then, as in many other books on the subject, she writes about the infamous loyalty questionnaire. Question 27 was asking if the person was willing to serve in the U.S. armed forces. Yes or No were the only blanks given. Question 28 asked if they would swear unqualified allegiance to the U.S., defend it from attack, and give up any allegiance or obedience to the Emperor of Japan. This was the questionnaire that result in those answering "no" to both parts being shipped off to the Tule Lake Detention Center.

The family moved once while they were still at Manzanar to a section that had been emptied by a family relocating outside of the camp (they had found employment) so this gave her family more room. Gradually they managed to make the area a little more livable. She then talks about how

the school finally got organized.

She mentions the Supreme Court cases that were heard at the time and the final ruling that the families were free to return to their homes, but at the time many were terribly afraid of going back to California, what with the intense racial hatred that was still there. Reports began to come back of those who had tried to resettle and of the shootings, beatings and house-burnings that met them when they got back to California.

Her father could not go back to being a fisherman since California passed a law in 1943 that made it illegal for Issei (first generation Japanese immigrants) to hold commercial fishing licenses. After that she writes about how her family basically had to start over from scratch.

She has a struggle in her own life, balancing her Japanese heritage with her desire to be fully American, and thus rejecting much of her Japanese heritage (not at all an uncommon event for the times, either).

She married outside her race, had children and once revisited the Manzanar site.

This is an extremely interesting book, especially since it's told by someone who had been through it all. There's enough historical information to put things into context, making this one of the more complete and best of the books on internment.

Main Index

Japan main page

Japanese-American Internment Camps index page

Japan and World War II index page

|