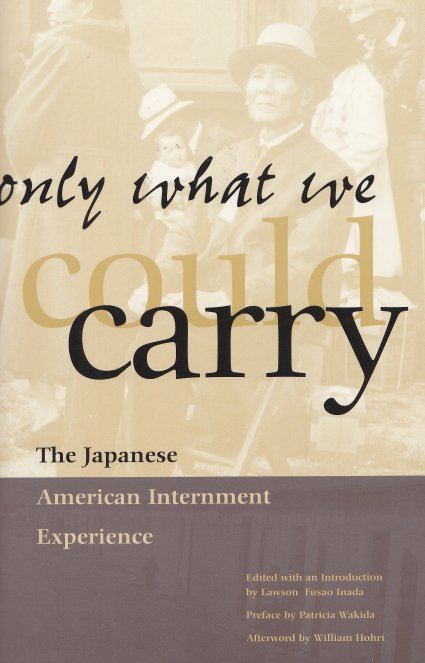

Only What We Could Carry

This is an unusual book on the internment process, as it consists of information, but also includes poetry, artwork, photographs, and personal remembrances, making it a very fascinating work.

The book starts right off noting that the U.S. suspended due process and put people of Japanese descent into what amounted to be prisons without any formal charges or trials, much less appeals. The book deals with the war years only.

One very interesting section is on editorials, which includes some from the Rafu Shimpo, a Japanese publication whose editors called on U.S. forces to crush the Japanese empire. One editorial from another newspaper said that “Racial hatred belongs in the arsenal of Nazi weapons and is used to inflict deep and biter wounds in the nations which Hitler would conquer.”

What is interesting is that these type of editorials happened in the time period after Pearl Harbor but, later, the Hearst papers stated their anti-Japanese campaign and the other papers changed their tune and went with the Hearst approach. One paper claimed that the moment Pearl Harbor was attacked Japanese worked quickly to block roads so the military people couldn't get to their stations. The paper even went so far as to claim that some ads had hidden codes the Japanese could decipher to help in their plot against the U.S.

Not a single one of the many, many rumors ever proved out to be true.

One thing that was true was that the Japanese could use the U.S. attitude towards blacks as a propaganda tool of their own, warning Asians they would be treated just as badly, that the war was a racial war against white oppressors.

There's an interesting breakdown of military exclusion zones, meaning all persons of Japanese descent had to move out of them. There was, of course, Military Area 1 and Military Area 2. There were also 84 other places in California, 7 in Washington, 24 in Oregon, and 18 in Arizona. This doesn't count 135 others around harbors, dams, power plants, etc.

There's a lot of interesting photographs of posters, magazine pieces, and even of the Tanforan racetrack assembly center which would pretty much disprove anyone who said that those in the assembly centers had pretty good living conditions.

There also happens to be an entry by George Takai, Mr. Sulu of Star Trek fame.

One very, very interesting thing. There was a newspaper comic strip of Superman, and part of that strip involved the visit of Clark Kent and Lois Lane to one of the internment camps. The military representative was trying to get them to believe how great the camp was, while Superman was able to detect trouble with his X-ray vision, a plot of some of the inmates to kidnap Clark Kent, Lois and the military rep.

The author of the book notes that he tried to get permission from DC comics to run a sample of the strip, and that they were the ONLY publisher they had contacted (and they must have contact a pretty large number, considering the variety of things in the book) that refused to give their permission to use any of their material.

Many of the governors of Western states did not want internees in their states, but the governor of Colorado was willing. He pointed out that there were 1,118,000 people in Colorado, and they could handle any number of internees that would be put there.

What most books don't do, but this one does, is talk about what happened to persons of Japanese ancestry in Canada, Mexico, Central and South America, Haiti and the Dominican Republic.

The difference in Hawaii is noted, with only 59 families evacuated a year after Pearl Harbor.

There's a chapter on the draft resisters at the Heart Mountain camp, and discussion about the Nisei who did end up in the US military and what jobs they filled.

The book is over 400 pages long and is one of the most unique and most interesting books that deal with the internment.

Main Index

Japan main page

Japanese-American Internment Camps index page

Japan and World War II index page

|