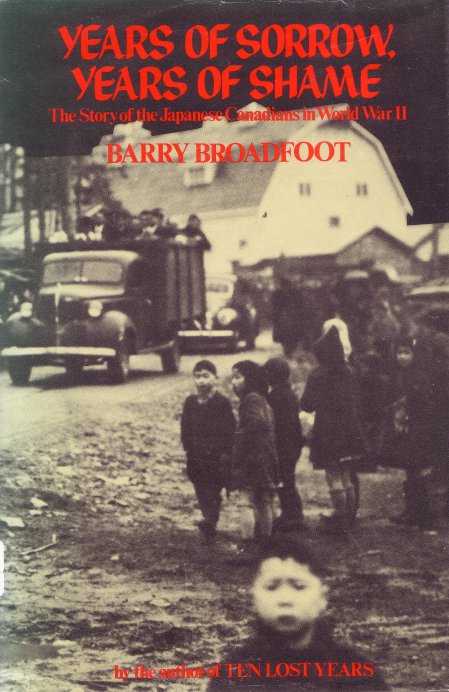

Years of Sorrow, Years of Shame:The Story of the Japanese Canadians in World War II (1977)

Basically, what happened in the US in relation to persons of Japanese ancestry happened in Canada with almost no major differences. There were similar racial and economic hatreds; similar fears, and a similar government reaction.

One of the actual differences simply lies in the number of camps. Whereas in the US there were around ten regular camps plus various FBI, Justice Department and military camps set up, in Canada there was Angler and various ghost towns. The evacuees were used to build roads, help the sugar beet crop and basically do the same kinds of things they did in the US. There was also the same effort on the part of the government to relocate the internees, spreading them throughout the country.

As in the US, most of the people evacuated and interned were citizens of the country.

The book points out a similar history of anti-Japanese feeling. In 1907 there were Oriental riots in Vancouver; somewhat of a misnomer since it was the whites who rioted, led on by a minister, and they sacked Chinatown. When they got to the Japanese portion of town, though, they met resistance and the riot broke up.

As in the US, there was the same type of discrimination in being served as blacks and Japanese Americans found in the US. One example given was when some Japanese Canadians tried to eat at a restaurant called The White Lunch and were met with the yell “Stay out of here, you Japs” from one of the cooks. In theaters there were sections (high up) for the Japanese Canadians to sit.

As in the US, persons of Japanese ancestry were forced to register and the community leadership (just as the JACL in the US) said to go ahead and do that, it will help prove how loyal they are. The still ended up being interned, though.

As in the US, Germans and Italians were not forced to register and were not interned in large numbers.

As in the US, without hours after the bombing of Pearl Harbor, persons of Japanese ancestry were being rounded up. Fishing boats were confiscated and livelihoods ended.

As in the US, evacuees were placed temporarily into horse stalls at Hastings Park, some 20,000 of them.

A lot of people were put onto road work, involuntarily, which helped to lead to a breakdown of the family structure. The roads were being built for military traffic.

A description of the Angler camp calls it a “prison camp” where there were guard with machine guns.

About 2,000 men were sent to the road-building camps; 3,400 were working in the fields of Alberta and Manitoba, and 1,000 were working elsewhere. 12,000 were sent to renovated ghost town at Sandon, Kaslo, Greenwood, Salmo and New Denver.

A parallel to the US plan to keep the Japanese Americans out of the west coast:

”It is vital to understand that the federal government had no intention of ever allowing the inhabitants of the ghost towns and camps to move back to the West Coast. On the contrary, th Japanese were to be scattered across Canada, each province taking its share-and thus would be eliminated the Japanese Problem in B.C. “

There was also a very similar military thing going on. In the U.S., the Nisei were not wanted as volunteers for the military at the start of the war; later, they were drafted into the military.

”Prior to Pearl Harbor no Japanese Canadians living in B.C. Were called up, and no volunteers were accepted. When Hastings Park began to fill up in early 1942 any number of young Japanese pleaded to join the army, even if they had to serve in a lowly labour battalion. They were refused. Instead, they were sent to road camps and ghost towns.

”But in 1944 the tide of war was changing in the Pacific and the British desperately needed men who spoke Japanese to be translators, interrogators, broadcasters.”

One problem, similar to that in the US, was that many of the Nisei did not speak Japanese and had to be given lessons. Unlike in the US, the fact that there were Nisei working in the Canadian military was not publicized until Sept. of 1945.

On August 4, 1944, the Prime Minister of Canada said that “no act of subversion or sabotage had been found before or during the war by the Japanese [Canadians]”. Exactly the same thing that happened, or didn't happen, in the US. At least in Canada they didn't have any officials saying things like “since there's been no sabotage then that's proof that there will be.”

Around 3,700 Japanese nationals in Canada repatriated to Japan in a program that was poorly run and extremely confusing.

Before the war there were 22,000 Japanese Canadians living in British Columbia. Afterwards, there were only 7,000, the rest being dispersed throughout Canada or returned to Japan.

Main Index

Japan main page

Japanese-American Internment Camps index page

Japan and World War II index page

|