Noh

The history of the Noh

Noh (sometimes spelled as No) is a very traditional form of Japanese theater dating all the way back to the 14th century. Actors (usually male) will chant and sing their roles accompanied by a chorus and an orchestra of flute and drums. There is little in the line of stage props although the masks and costumes themselves can be lavish. The movements of the actors are slow and deliberate.

The origins of Noh go back to Central Asian dance and mime forms. One type is the sangaku which combined music, dancing and sometimes even juggling. It was brought into Japan from Korea and China in the early 8th century. The word was altered to sarugaku ("monkey music") by the middle of the 14th century.

Forms native to Japan were also used. One was dengaku ("rustic music") which was a folk-dance ritual used during rice planting and harvesting times. Another form was kagura which is a religious dance performed at Shinto shrines.

The term Noh itself is a Buddhist term which refers to the mental bond between the performers and the audience. By the 14th century it was the major form of entertainment of court nobility. Terms that were used then included saragaku-no and dengaku-no, the no part being used to indicate that the performers were professionals and not amateurs.

By the late 14th century the term saragaku-No was being used and the dangaku-no part dropped, it's part being absorbed into the saragaku-no portion.

Troupes of performers were usually attached to Shinto shrines and Buddhist temples. Sometimes the actors were low-rank priests and they would even at times go on tours, giving benefit performances.

Noh (sometimes spelled as No) is a very traditional form of Japanese theater dating all the way back to the 14th century. Actors (usually male) will chant and sing their roles accompanied by a chorus and an orchestra of flute and drums. There is little in the line of stage props although the masks and costumes themselves can be lavish. The movements of the actors are slow and deliberate.

The origins of Noh go back to Central Asian dance and mime forms. One type is the sangaku which combined music, dancing and sometimes even juggling. It was brought into Japan from Korea and China in the early 8th century. The word was altered to sarugaku ("monkey music") by the middle of the 14th century.

Forms native to Japan were also used. One was dengaku ("rustic music") which was a folk-dance ritual used during rice planting and harvesting times. Another form was kagura which is a religious dance performed at Shinto shrines.

The term Noh itself is a Buddhist term which refers to the mental bond between the performers and the audience. By the 14th century it was the major form of entertainment of court nobility. Terms that were used then included saragaku-no and dengaku-no, the no part being used to indicate that the performers were professionals and not amateurs.

By the late 14th century the term saragaku-No was being used and the dangaku-no part dropped, it's part being absorbed into the saragaku-no portion.

Troupes of performers were usually attached to Shinto shrines and Buddhist temples. Sometimes the actors were low-rank priests and they would even at times go on tours, giving benefit performances.

The Noh, as it is today, is considered to have been begun by Kannami (who was the leader of one of the performing groups at Kasuga Shrine at Nara) and his son, Zeami (sometimes written as Seami)(1363-1443). Kannami performed before a wide group of people, ranging from farmers on up to nobles. He had an ability to adjust his performance to suit the particular type of audience he was performing before.

He gave a performance at a shrine in Kyoto in 1374. One of the people in the audience was Yoshimitsu, the effective ruler of Japan at the time. Yoshimitsu loved the performance, especially that of Kannami's twelve-year-old son Zeami, so he established the troupe in his palace. He thus became their patron.

Upon Kannami's death, Zeami took over the troupe. Yoshimitsu's sons and successors weren't as favorably disposed to him as Yoshimitsu, though, and Zeami ended up being exiled in 1434 to a distant island by Yoshimitsu's youngest son.

Zeami was a prolific writer and around 100 of the 241 plays known at the time. He also wrote sixteen essays on the subject of Noh. They two established the basic principles of Noh performance. There would be four or five actors; the main speaker/dancer, one person who does not dance (oftentimes a priest figure), and other individuals. The ending of each play would consist of a dance. Although the plays would not have a great deal of dialogue they would still take an hour or so to perform due to the dances and the deliberate pace of speaking what lines there were.

About a thousand plays were written during the Muromachi period, but some four hundred of those no longer exist. The two-hundred and fifty or so plays used today were almost all written during that period.

One of the first non-Japanese to see a Noh play was no other than Ulysses S. Grant, civil war hero and one-time President of the U.S. Grant apparently liked the play and urged his Japanese hosts to make sure that such plays were preserved.

The philosophy of Noh

Zeami emphasized poetry to the actors. He said that the poetry used needed to be familiar to the audiences in order to be effective, and that actors should study poetry to help them learn give a more elegant and graceful aspect to the delivery of their lines.

Zeami also said that there were three guiding principles for Noh, the first being imitation. The actor, he said, must be able to imitate things as they are, and not to embellish the things with extra forcefulness, elegance or anything else not found naturally in the thing being imitated.

The second principle is Yugen, which is based on the idea that Truth is Beauty, and that the beautiful aspect of anything can be brought out if acted skillfully enough. It's the beauty that lies at the heart of things, he said, and can "...be evoked by means of art."

The third element of Noh is the sublime. This refers to a things "silent, stately, austere beauty". He says that there were three kinds of the sublime; the Style of a Calm Flower, the Style of an Infinitely Deep Flower, and the Style of a Mysterious Flower.

An example of the first kind is snow in a silver bowl, united in a "purity of whiteness", which is basically a physical sort of beauty. The second kind can be something like a series of mountain peaks covered in snow, but with one single peak uncovered. This is more of a supernatural type of beauty, and the third refers to the "realm of the absolute", a Zen reference to a place without good, evil, right, wrong or any of the other similar things used to pigeon-hole people and things.

The order of the plays

The program has a traditional order which is called Ban-gumi. The first is a god-play, also referred to as the Shugen or congratulatory piece. This type comes first, in praise and prayer to the gods since they have guarded Japan from time immemorial. This part is the "innocent" phase, a world with divine blessings and where man and gods live together.

The second part is the shura, or battle-play where the ghost of a warrior appears. This is also referred to as the Man play and the "fall" play. In this one a warrior who was distinguished in battle is now dead and suffering in hell. His emphasis was on worldly honor and he did not recognize a higher form of honor. This play is also characterized by violence and chaos.

The third section is the Kazura or Onna-mono, the wig-play, where the principal character is a woman, this giving this the name of the Woman play, also called the Repentance play. The woman in this case is usually a lovely court lady, who lead a basically good life but still, for some reason, her soul haunts the world, oftentimes in an act of repentance.

The Oni-Noh is the fourth piece and is the play involving spirits. It can also be referred to as the Frenzy play or the Redemption play. The play revolves around humans, and shows that miracles can happen in the "real" world, and that a soul can be redeemed.

The fifth piece concerns the duties of man: Jin, Gi, Rei, Chi and Shiro which are Compassion, Righteousness, Politeness, Wisdom and Faithfulness. It can also be called the Glory play.

The Sugen comes sixth and is another congratulatory piece. This is to call down the blessings of any lords present, the actors and the place itself.

(Note: there is some disagreement about the above in the various sources I consulted, so what I have here is not a cut-and-dried description of Noh.)

Today, though, a performance may contain only two plays and a comic interlude called a kyogen, the use of the kyogen also being present in the longer performances.

Technical terms in Noh

There are a number of technical terms used in Noh. Among these are:

Shite: The hero or chief character

Tsure: The follower of the hero.

Waki: the guest or guests, oftentimes a wandering priest.

Waki no tsure: the guest's attendant.

Tomo: an insignificant attendant.

Kogata: a very young boy.

Kiogenshi: a sailor or servant.

Hannya: an evil spirit.

Kataru: the speaking parts of Noh

Utai: the singing parts of Noh

The two main characters in the plays are the waki and the shite. The shite is given the best lines. The characters in the plays do not get as fully developed as those in some movies and television series, though. The purpose is to reduce complexity to a basic distillation or essence of human behavior.

Noh plots

The first basic division of types of Noh plots is found in those which are set in the real world, and those that involve some form of supernatural being.

The real world plots can include plays where long-separate parents and children or brothers and sisters finally get to meet, the meeting brought about or aided by a priest or even a diety.

Most of the plays are of the second type. These are divided into two parts. In the first part of the play, the waki, often a monk or priest, meets the shite at some special place.

The monk, being an agent of Buddha, has no set individuality or mentality. His function is as a medium between the actions on the stage and the audience, similar to his function as a medium between Buddha and man.

The shite, or protagonist, is often the departed soul of a sinner who has come from hell asking for help. The sinner initiates the contact; he has come to recognize his sin and transforms himself so he can enter our world and find a means of salvation.

The monk and the shite talk about why the place is special; perhaps some historic battle took place there or some tragic love affair ended there. The shite seems to be extremely knowledgeable about what happened at the place, though. As the story progresses the shite becomes more emotional, finally confessing his sin and asking the monk to pray for him.

The shite exits, and a short kyogen interlude occurs. While this is going on the actor playing the shite changes his costume and his mask and when he appears in the next part of the play it is as his "real" self. The differences between the two versions can be considerable, with the shite chancing from a beautiful girl into a serpent, or perhaps a boy changes into the spirit of a warrior.

In this second part the shite, aided by the chorus, tells of his history, and climaxes this by a dance. The warrior, for example, might basically re-enact a great battle in which he participated. A woman might have had some form of illicit relationship and now is wearing the mask of a demon. The priest, monk or diety might then pray for the repose of the spirit of the person.

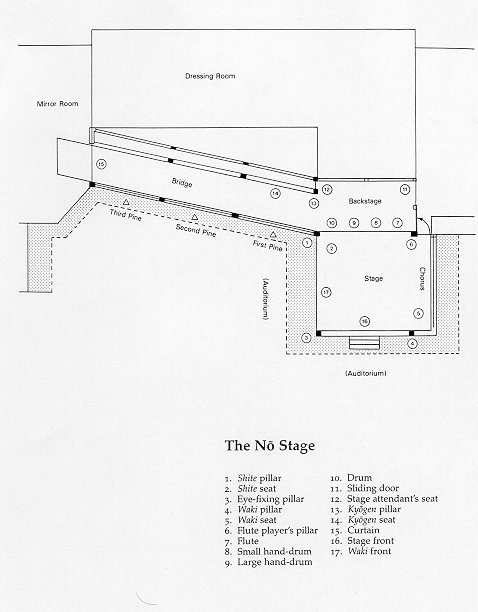

The Noh stage

The basic form of the stage was fixed during the times of Hideyoshi and Iyeyasu. The area underneath the stage will have five earthen jars to make the sound of the singing and feet-stamping reverberate. These five jars are in the areas bounded by the pillars. Two more jars are under the musician's area, and three more under the bridge. The ground underneath the stage is hollowed out to a five-foot depth.

The Noh stage is not going to be filled with various props like you might see in an American play. Even when an object is on the stage, it's exact form is not. A tomb, for example, might be represented by four upright poles topped by greenery. In relation to the distillation-approach of Noh, the object appears in a reduced form, represented by what amounts to outlines of the "real" object.

Objects can also be used as indicators. A woman might carry a twig of bamboo, the bamboo used to indicate her insanity.

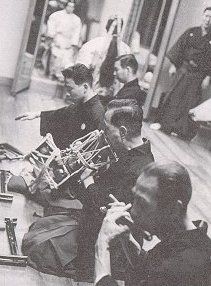

The music for the Noh is presented using the above instruments. Going from left to right there is the daiko, or stick-drum; the otxuzumi and the kotsuzumi, or hand drums, and the fue, or flute.

The backstage area can be as busy as any Western-style theater, as is shown in the picture below where the shite and the musicians prepare to go on stage.

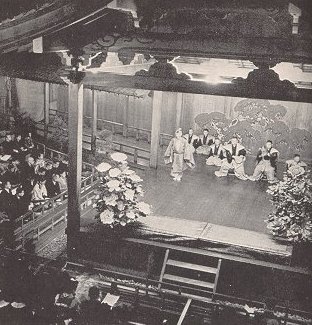

A more modern-day Noh stage.

The stage will also probably have a painting of a pine tree on a backdrop. The pine is a symbol of strength and the eternal. Long ago, according to legend, a priest was seen dancing under a pine tree, seeking to have divine inspiration added to his dance. The painting of the tree thus symbolizes a request for the same sort of inspiration for the play.

The performance

1. The actor makes his entrance. Previously, he had been standing in the mirror room where he looked into a full-length mirror to help him get in character. He leaves the room and the curtain between the mirror room and the stage is lifted from the bottom by backstage assistants.

2. The actor moves to the bridge area, railed on either side, about 6.5 feet wide and from 33 to 52 feet in length. The bridge is roofed. On the rear wall of the stage is painted a stylized pine-tree which serves as a reminder of the pine trees behind the stage of the Kasuga shrine in Nara.

3. Basically in slow motion the actor moves towards the stage proper. He slides his feet alone the floor. When he reaches the stage proper he passes a pillar referred to as "the pillar of the principal character."

4. The actor then usually moves towards the front of the stage. Since he is wearing a mask, it's difficult to see exactly where he is going so he focuses on a downstage pillar, called "the pillar on which the eye is fixed." Opposite on the stage is the waki's pillar since the subordinate character places himself near that pillar when the principal character makes his entrance.

On the left side of the stage is an area about 4 feet wide where six or eight members of the chorus sit, having entered through the Hurry Door, a door in the upstage-left corner of the stage and also used by lesser characters.

The Noh costume

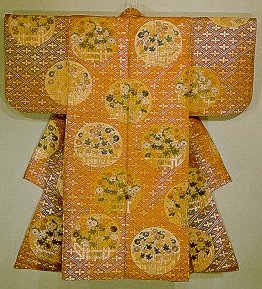

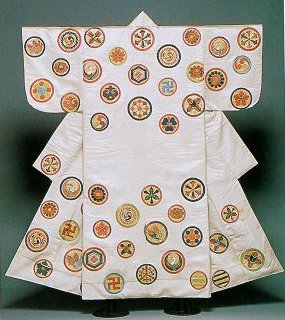

The oldest surviving Noh garments date from the 15th century during the reign of the sixth shogun, Yoshimasu (reigned 1440-1473). The particular costume worn by the actor depends on the role played. Thus, a certain kind of costume indicates a certain kind of character type such as a young woman, a handsome man or a demon.

The color of the Noh costumes is important. White is considered to be the most dignified color and is used for characters of nobility. Brown is considered to be the least dignified color and is used for servants and country people. Red is worn by young girls and older women wear darker colors. Light blue indicates a quick temperament. Dark blue indicates an extroverted person. Light green is used for menials.

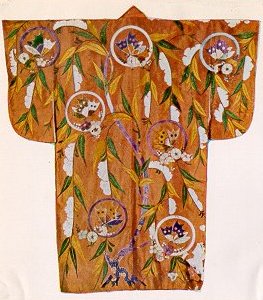

One of the types of costumes is the kara-ori. It is usually worn to indicate a female but sometimes can be used to indicate a very elegant young man. An example is below:

This costume is from the early 17th century

Another 17th century Noh costume worn for a female role.

Other types of costumes include the atsuita, for male roles. Another type of costume is worn to indicate aristocratic gentlemen, Shinto priests and divine beings and is called the kariginu. Costumes used to indicate deities and men of high rank are lined, the ones worn to indicate Shinto priests are unlined.

Undergarments used when playing female roles are referred to as nuihaku and surihaku. A kara-ori is worn over these. An example of a nuihaku from the mid-Edo period is below. The nuihaku is can be used for courtiers, youths or children

A common jacket used for male roles is the happi; this is a knee-length garment with long hanging sleeves which are folded back.

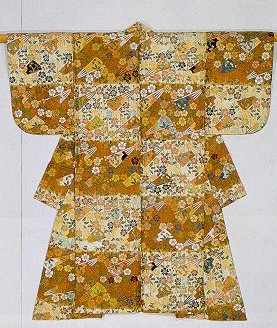

It seems to be generally agreed that the costumes declined in workmanship and quality as time went on, with the best ones being made in the Momoyama period and the early Edo period. Mid-Edo period costumes are considered still to be good, but in the 19th century the costumes declined sharply in quality. Noh garments are still made today but are not considered to be anywhere near the Momoyama garments in quality.

An example of a costume from the Momoyama period is below. It's quite interesting and attractive in design and in my opinion looks like something from modern times. It's hard to believe that it is actually as old as it is.

Then, still in the "highest-quality" time period for costumes there is the one below, made during the early part of the Edo period. It is classified as a Nuihaku or embroidered costume. The ships are Dutch sailing ships; the waves are in gold leaf and the ships and flowers are embroidered.

Below is a kara-ori from the late Edo period with fans and the branches of a weeping cherry tree.

A 17th century Noh robe with an iris pattern. In my opinion this is a beautiful costume. The bright orange color overall and the various colors of the plants seem to go together well.

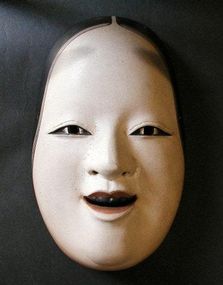

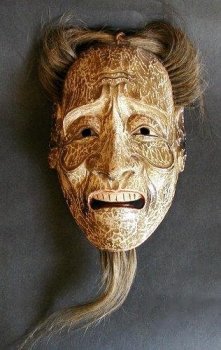

Noh masks

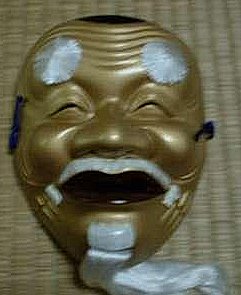

Noh masks are classified into a number of types which include men, women, deities and sages, insane people, devils and mythological creatures. The mask was expected to display an essential quality of each character such as beauty for a woman. As early as the start of the Edo period Noh masks were established in their detail and ones afterwards were exact reproductions of the earlier forms.

The okina mask portrays a very old man. Its origin is supposed to be around 806-810 where a huge hold appeared in the ground at Nara. A dark smoke came from the hole and as it spread people became ill. The Emperor called together various wise people and it was determined that it was necessary to build a big fire around the hole. This was done and the dark smoke disappeared. A celebratory dance was performed and it became a tradition. The oldest okina mask which is from 1206 is preserved in the Asakusa temple in Tokyo.

Some other Noh masks include those of Kagekiyo (a warrior); Yamauba (a witch); and Uba (old woman).

Although the names of the ten most famous Noh mask-makers are known, virtually no biographical information is available on any of them.

Various Noh masks

A Noh mask from the 17th century.

Obviously a mask to represent a female character.

Obviously a mask representing an old man.

This is a wooden Noh mask from the Meiji period (1867-1911). It is of the character Ko-omote, an unmarried woman. Ko means beauty and youth and omote means face. The mask is used to portray a noble woman or a lover who dies in her prime.

These is a picture of a Noh mask from the late Edo period. The mask is of a character named Ko-Jo, or old man. Ko-Jo was named after its creator Koushi. He appears in elegant scenes as a distinguished character.

Other information

The term waka refers to Japanese court poetry. Knowledge of this was considered to be essential for a refined/cultivated person.

Renga refers to a linked verse form of poetry which supplanted the waka form over time.

Noh and Kabuki References

Heaven has a Face; So Does Hell : The Art of the Noh Mask; Stephen E. Marvin, 2009

Noh: The Classical Theater, Yasuo Nakamura, 1971.

The Classic Noh Theatre of Japan; Ezra Pound & Ernest Fenollosa. 1959.

The Kabuki Theatre, Earle Ernst. 1956.

The Noh drama; ten plays from the Japanese selected and translated by the Special Noh Committee , 1960.

Noh, or Accomplishment: A Study of the Classical Stage of Japan (1916)

The Noh Plays of Japan (1922)

The Noh Plays of Japan; Arthur Waley; 2009.

The Noh Theatre of Japan:With Complete Texts of 15 Classic Plays; Ernest Francisco Fenollosa, Ezra Pound; 2004.

The Traditional Theatre of Japan: Kyogen, Noh, Kabuki and Puppetry; John Wesley Twelve Plays of the Noh and Kyogen Theaters; Cornell University East Asia Papers Number 50; Karen Brazell (ed.) assisted by J. Philip Gabriel; East Asia Program | Cornell University, Ithaca, NY, (1990).

Main Index

Japan main page

Japanese-American Internment Camps index page

Japan and World War II index page

|