Japanese Americans: Home at Last

National Geographic, April, 1986

On the day in May 1942 when American soldiers took her and her family to the concentration camp, the very last thing Mary Tsukamoto did was sweep the house. "I had to leave it clean," she explains. "We didn't know how long we'd be gone."

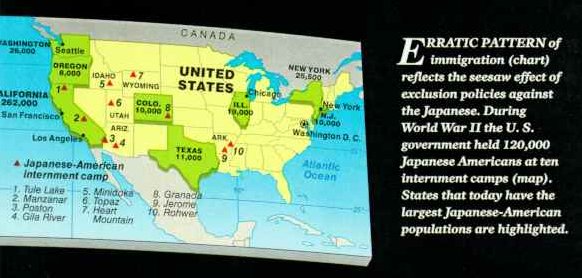

Mrs. Tsukamoto was one of nearly 120,000 American citizens and alien residents of Japanese ancestry who, after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, were uprooted from West Coast homes, farms, and businesses and herded, most of them, into assembly centers in racetracks and fairgrounds. Later they were transported to ten desolate concentration camps-the term used by President Franklin D. Roosevelt himself, whose Executive Order 9066, signed February 19, 1942, put them there.

Categorized by this presidential action as potential spies and saboteurs, they remained behind barbed wire for an average term of two and a half years. The ordeal devastated the life's work of Issei (first generation Japanese in the United States), costing them millions in lost property and income. It deprived their Nisei (second generation) offspring, born in the U.S., of liberty and the rights of citizenship. It fractured families along political and generational lines. Above all, in branding them as disloyal without charge or trial, it inflicted on Japanese Americans a gnawing sense of shame–for some to the third and fourth generations.

In the years since the war Japanese Americans have surmounted most of the social obstacles erected against them. They have risen so high and so fast, in fact t, that they have been called a model minority–an epithet they deplore as simplistic, condescending, and forgetful of their traumatic history in the United States. Dr. Ford H. Kuramoto, director of Hollywood Mental Health Service, calls the stigma of internment "a psychic skeleton in the closet."

Mary Tsukamoto, retired now after 26 years of teaching in Florin, California, still loves to talk to children of Japanese ancestry about old country culture. "They look up at me with their big eyes," she relates, "and ask, again and again, ‘Was Great-grandpa really guilty when they put him in the concentration camp?'"

Windblown and seasick, 18-year-old Yuki Torigoe stood at the rail as the salt-caked steamer Siberia Maru slipped through the Golden Gate into San Francisco Bay. Like a score of other "picture brides" descending the ship's gangplank, she looked from her husband's photograph to the faces of the men in the dockside throng. It was May 1914. Less than a month before, at her home in Kurashiki, she had knelt before a Shinto altar in her finest kimono and married, by proxy, a man she had never met–a man who was then 5,500 miles away, running a small shop in Watsonville, California.

"Somehow we all just found each other," Mrs. Torigoe, now 90 and widowed, remembers. "Some of the other brides were crying. Their husbands turned out to be 20 years older than their photos. But we all went off in cars for a mass American wedding at the hotel."

Of the 214,000 Japanese immigrants who arrived in the United States in the first two decades of the 20th century, fewer than 30,000 were women. Perhaps half were picture brides; most were a decade or more younger than their husbands. Many immigrants were impoverished farmers from southern prefectures like Hiroshima. But they carried in their hearts a fierce pride in Japan's rising power, a profound commitment to the stern, traditional values – on (duty to family and country), girl (a moral indebtedness, as to a parent, that cannot be repaid), gaman (stoic endurance)–and a burning determination to work hard in America, make good, and return to their beloved homeland.

"They had no intention of staying," Yugi Ichioka, researcher at the Asian American Studies Center of the University of California, Los Angeles, explains. "They were sojourners–birds of passage."

American did not invite them to stay. As Asians they were barred from U.S. citizenship–"the single most important factor affecting the Issei in this country," Ichioka avers. "It kept them out of the American political process and left them defenseless against discriminatory legislation."

From 1907 through 1948 anti-Japanese bills were introduced in every session of the California legislature. In 1902 a gentleman's agreement between the United States and Japan halted immigration of male laborers. In 1913, a California law banned purchase by land of aliens "ineligible to citizenship." Seven years later a similar law prevented them from leasing land. Then, in 1924, a new U.S. Immigration Act slammed the door on Japanese immigration completely.

The Japanese settled for whatever wages they could get–often half what whites were paid for similar labor. Most turned to farming, laboring under Japanese bosses in picking, packing, and pruning gangs that began work by lantern light well before dawn and finished long past dark.

Michiko Tanaka, who left Hiroshima for California in 1923 and bore 13 American children, recalls the life. "Until the internment camp, I worked in the fields right up to the day each baby was born," she says. "We would finish the work, wrap our children in blankets–and move on. Papa loved to gamble and drink. All the Issei men did. Me, he never talked to. The children, Papa harangued: ‘Learn your culture! Learn Japanese! As long as you look Japanese, you are going to be Japanese.' "

"Papa knew the struggle was futile–that as long as we lived her Americanization was going to gobble us up," says the Tanaka's daughter Akemi Kikumura, a cultural anthropologist. "But he fought it as long as he lived. That was my father's way."

Nonetheless, the Issei sought places to put down roots. Some managed to buy or lease farms before alien land measures passed into law. Some put titles in the names of their American-born children or of trusted American friends. In all, the Japanese never owned or leased more than 4 percent of California's improved cropland. But by 1920, sales of Issei farm produce amounted for more than 10 percent of the total value of all commercial truck crops in California.

"Japanese neighborhoods grew up as sanctuaries against outside hostility," Dr. Kikumura goes on. "They became, in effect, extended families." The Japanese community in San Mateo, south of San Francisco, was typical. By 1924 the town had both a Buddhist and a Christian church. A chapter of the Japanese Association of America was resolving commercial disputes and staging annual picnics. There were six billiard parlors and an apartment house complete with backyard tea garden and redwood o-furo (hot tub bath), where Issei men gathered on Saturday nights to soak away cares, sip sake, and strum the samisen (three-stringed banjo). Tanomoshi, an informal savings and loan system, helped provide capital for local businesses serving local needs. "Default meant disgrace to the borrower and his family," Dr. Kikumura explains. "No one would have dreamed of it."

For boys, most communities had a Scout troop, a baseball team, and a kendo (Japanese fencing) and sumo (wrestling) club. Girls joined the Camp Fire Girls and odori (Japanese dance) groups. Nisei males, growing up in this mixed world of old Japan and new America, were separated from their fathers by an average age difference of 38 years. Three-fourths of the parents were Buddhist; most knew little English. the majority of the children were Christian; all spoke English, and few spoke Japanese.

Parental word was law. There was virtually no juvenile delinquency. Teachers ranked second only to parents. "Honor or shame to the family name would be brought according to the success or failure of the child in school," wrote Seattle sociologist S. Frank Miyamoto. After-school Japanese-language classes only created more cultural conflict. Retired U.S. Army Maj. Tom Kawaguchi, 64, director of Go For Broke Inc, a Japanese-American veterans' organization based in San Francisco, tells how one Nisei saw it; "I hated every minute of it. I wanted to be an American!"

This sentiment was shared by many members of the influential Japanese American Citizens League (JACL), founded in 1929. Issei, denied U.S. citizenship, still looked on Japan as their motherland, still felt its emotional tug. But their Nisei sons and daughters adopted the JACL credo: "I am proud that I am an American citizen of Japanese ancestry," and they pledged to defend the United States "against all enemies." Seattle Issei Yoshisada Kawai articulated the Issei's dilemma: "I felt a turmoil deep in my mind," he told an interviewer at 81. "I did not want my sons to take arms against my mother country. But I owed this country a lot. I was crushed between human affection and giri."Kamechiyo Takahashi, 94, of San Mateo, recalls her own family circumstance: "We'd saved a goodly amount over the years to build a home of our own. Then, when it looked as if war was imminent, Mr. Takahashi said he thought we should take the money and go back to Japan. But out two sons said: ‘Wait! We're Americans! Our world is here.' So we built our house and then moved into it in the fall of 1941."

Just a few weeks later Mrs. Takahashi, busy in the kitchen, heard a radio blaring in the living room. "I couldn't understand the English," she recalls. "All I could hear was the announcer shouting." It was Sunday, December 7.

"Just visualize that day! The Pacific Fleet, our first line of defense, was all but sunk! Our second line was the West Coast, where the heaviest concentration of Japanese and people of Japanese descent resided. And we were getting it straight from the horse's mouth–from intercepted cable traffic out of Tokyo, which we code-named MAGIC-that the Japanese were setting up an espionage-sabotage network on the coast. There was only one thing to do, and that was move those people out of there."

The speaker is New York lawyer John J. McCloy, 91, Assistant Secretary of War under President Franklin D. Roosevelt.

"Earl Warren, the attorney general out there in California (afterward Chief Justice of the United States) had been pleading with the White House; ‘For God's sake! Move the Japanese.'

"The President called Francis Biddle, the Attorney General, into his office.

"Francis," the President said, "are you in favor of this move?"

"Oh yes, Mr. President," said Biddle. "But I want to see it carried out humanely."

"That's exactly what I want to do," the President said. "You helped draw the order"–and right then and there, Biddle did. The President went on: "And I want the Army to carry it out."

"When he heard of the plan, Chief of Staff General George Marshall pleaded:'Please, Mr. President, we've got our hands full.'

"No," said the President, "No civilian agency can do this. I want the Army to take it on."

"We were faced with what Mr. Churchill called the "bloody dilemmas." I said, "We're going to have litigation about this, but we better go ahead and do it. We don't know where their next attack is coming from." I didn't give a damn whether they were citizens or not."

Scholars have questioned the necessity of President Roosevelt's action, pointing out that the Office of Naval Intelligence, the Federal Bureau of Investigation, and President Roosevelt's own special investigator all assured Washington that there was no evidence of espionage or sabotage by Japanese Americans. Dr. peter Irons, associate professor of political science at the University of California, San Diego, who conducted an exhaustive study of 2,000-plus MAGIC messages, concludes:"The MAGIC cables do not implicate Japanese Americans in any sabotage or espionage activity. They provide no substantiation for concern on the President's part about the loyalty of Japanese Americans on the West Coast."

"We're charged with wanting to get rid of the Japs for selfish reasons," said the secretary of California's Grower-Shipper Vegetable Association in the Saturday Evening Post in May 1942. "We do."

Declared U.S. Congressman John Rankin of Mississippi: "This is a race war." But whatever else is said, ultimate responsibility was the President's. As McCloy states: "Franklin Roosevelt was the only man in the world who could sign that order relocating those people. And he signed it." Reflected Attorney General Biddle in his memoirs: "The Constitution has never greatly bothered any wartime President."

On the West Coast, FBI agents and local police rounded up more than 2,000 suspected security risks; Japanese-language and martial-arts teachers, Buddhist priests, community leaders. Among the targets were picture bride Yuki Torigoe and her husband, who ran a small watch-repair and gun shop in Watsonville, California. "That very morning they took Mr. Torigoe away. I didn't seem him again for nearly a year."

The President's order had little effect on Hawaii. Fewer than 2,000 Japanese were taken into custody. Hawaii's 158,000 Japanese represented 37 percent of the population an even higher percentage of the skilled labor force. "Without them," says Franklin Odo, director of ethnic studies at the University of Hawaii at Manoa," Hawaii simply couldn't have functioned."

A civilian War Relocation Authority (WRA) was established to assist in the evacuation. It's first director, Milton S. Eisenhower, brother of the general, envisioned the agency overseeing a humane resettlement program that would put the uprooted Japanese back to work in public and private jobs throughout the inland states. But the reception Eisenhower received at a meeting with the governors and attorneys general of ten western states on April 7, 1942, convinced him that such a scheme had no hope of realization. Wyoming Governor Nels Smith warned that if Eisenhower's plan were attempted, "there would be Japs hanging from every pine tree." Explained Idaho Attorney General Bert Miller: "We want to keep this a white man's country." Eisenhower resigned.

"So," says Yuji Ichioka, "the great fire sale got under way." Evacuation notices, posted on telephone poles, gave some Japanese just two days to dispose of the possessions of a lifetime. A few, like Mary Tuskamoto and her husband, were able to leave homes and property in the care of trusted friends. Most had to deal with bargain hunters and profiteers.

Mary Oda's family, who farmed 30 acres in the San Fernando Valley, had just two weeks to dispose of a new $1,200 tractor, three cars, three trucks, and all their crops. "In all," recalls Dr. Oda, now a physician practicing near the former family homesite, "We got $1,100. We couldn't argue. We had to leave."

When evacuation day arrived, Normal Mineta, who was then ten and later became a U.S. congressman from San Jose, put on his Cub Scout uniform. At the 1942 commencement exercises of the University of California at Berkeley, the top scholar was absent. Harvey Itano, who recorded four years of straight A's, was in the Sacramento assembly center. Explained university president Robert G. Sproul: "His country has called him elsewhere."

Hoping thereby to prove their patriotism, the majority of Japanese Americans went off to the internment camps without a whisper. Exhorted JACL president Saburo Kido: "Let us leave with a smiling face and courageous mien. Let us look upon ourselves as the pioneers of a new era looking forward to the greatest adventure of our times."

"Like a lot of couples then, we got married just before the evacuation so we wouldn't be separated," remembers Dr. Kazuyuki Takahashi, retired now after 23 years in internal medicine at Oakland's Kaiser Hospital. Adds his wife, Soyo, "We honeymooned at Santa Anita assembly center."

The racetrack, near Pasadena, was converted into a holding area for Japanese American, pending construction of permanent concentration camps. At Santa Anita the Takahashis shared a single, manure-speckled horse stall, and one roll of toilet paper a week, with another newlywed couple. "Manure dust kept drifting down from the walls and ceilings" Doctor Takahashi relates. Soyo adds: "We had four wood-frame cots with straw-filled mattresses, jammed in crosswise with a blanket hanging down the middle for privacy. After a couple of weeks, mushrooms began growing up through the floor."

Kaz tacked up wrapping paper to block the manure dust. Soyo hung a Stanford pennant. "Something great and something American may come out of all this," young Kaz wrote in June 1942. "In the meantime we live on from day to day, not unhappily but in a fog of uncertainty about the future."

By September, ten camps had been constructed in the wilds of Arkansas, Arizona, California, Colorado, Idaho, Utah and Wyoming. Rohwer, Arkansas, was surrounded by mosquito-and snake-infested swamps and became a quagmire when the rains came. Poston, Arizona, got so hot that people jokingly named the camp Roastin', poured water on their canvas cots, and slept outdoors trying to keep cool-until dust storms drove them back inside.

California's Manzanar-where the Takahashis were moved in the fall of 1942-was typical: wood-frame, tar-paper barracks, armed guards in sentry towers, barbed wire. An American flag fluttered over the gates. Each barracks consisted of four 20-b-20 foot rooms furnished with an oil stove and a bare hanging bulb. There were no closets, Takahashi wrote, "no shelves, no table or chair, not even a nail to hang one's hat." Open showers and latrines offered no privacy.

Five doctors cared for the camps 10,000 people. Mary Oda lost her father, older brother, and a sister in the scant space of seven months. Tom Watanabe, now of Chicago, lost his wife and twin girls in childbirth. "What haunted me," Watanabe says, "was that for years I didn't know what they did with the bodies."

To ease the wartime labor shortage, the WRA allowed some internees to work outside th camps. The plan, for the most part, was successful-but not always. Nancy Araki and her parents left Amache, Colorado, to start a form at American Fork, Utah. "I slept on a sofa under the living-room windows," she recalls. "I was just falling asleep one night when someone threw a brick through the glass. My father moved us back into a camp."

The camps weren't trouble free either. "The air has been tense and explosive for the past several months," Takahashi wrote as the winter of 1942 set in. Small, pro-Japanese gangs were trying to have their way by a reign of terror, he explained. Some, though, not all of the Kibei-that is-American-born citizens educated in Japan-were openly pro-Japanese. The "thoroughly American" internees were keeping quiet because "we all realize that Americanism has somehow skipped the Japanese Americans..."

Two days before Pearl Harbor's first anniversary, one of the pro-American JACL leaders at Manzanar, Fred Tayama, was severely beaten. Three Kibei were arrested for the assault. Next day a riot erupted-the worse violence of the evacuation. Two internees were killed by military police, ten others were wounded. "We stayed in our quarters. We were frightened," Dr. Takahashi relates now.

To separate loyal from disloyal individuals, and to identify those who might be called up for military service, the government in February 1943 required internees over 16 to fill out a loyalty questionnaire. Question 27 asked Nisei males "Are you willing to serve in the armed forces of the United States, on combat duty, wherever ordered?" Question 28 asked "Will you swear unqualified allegiance to the United States...and foreswear any form of allegiance or obedience to the Japanese emperor...?"

Some 9,000 answered the questions "no-no", qualified their answers, or refused to respond at all. All persons giving so-called no-no answers were summarily branded disloyal. Most were eventually removed from their camps and segregated for the duration at Tule Lake, California. But more than 65,000, about 85 percent of the internees who responded, answered "yes-yes", affirming their loyalty. "It was my country and I wanted to defend it," says Tom Kawaguchi. "It was that simple." Explains Hawaii's Senator Daniel K. Inouye, who lost an arm in combat and earned the Distinguished Service Cross, America's second highest decoration for bravery, "We were fighting two wars-one against the Axis overseas and another against racism at home."

The 23,000 Nisei who fought for the country of their birth averaged five feet four inches in height and 125 pounds in weight, with M1 rifle and grenades. They wore shirts with 13 ½ inch necks, pants with 26-inch waists and size three boots. They won more than 18,000 decorations for bravery, including a Medal of Honor, 52 Distinguished Service Crosses, 560 Silver Stars, 28 with oak-leaf clusters, and no fewer than 9,486 Purple Hearts.

Nisei were barred from enlisting in the Navy and Marines, but 6,000 served as Army military intelligence specialists in the Pacific. They were attached to about 130 unites from eight different countries and the armies of China. According to Gen. Charles Willoughby, intelligence chief for Gen. Douglas MacArthur, they shortened the war against Japan by two years.

Their single most valuable exploit, says Shig Kihara, one of the founders of the Army's Japanese -language school at the Presidio in San Francisco, was cracking Operation Z, Japan's strategic plan for the defense of the Philippines and the Marianas. The result of that effort was the U.S. naval victory in the Battle of Leyte Gulf and the final destruction of the Japanese fleet.

in Europe, the mainland Nisei's 442nd Regimental Combat Team, combined overseas with the Hawaiian 100th Battalion, took for it's motto "Go For Broke." Fighting in Italy and southern France, the 100/442nd emerged for its size and length of service as the most decorated unit in American history-earning eight Presidential Unit Citations and taking 300 percent casualties.

Its most celebrated mission was the October, 1944 rescue of the "Lost Battalion"- a unit of the Texas 36th Infantry Division, which had been cut off and was being chewed to pieces in the Vosges Mountains of France. In furious fighting over six days, the 100/442nd suffered more than 800 casualties to rescue 211 members of the Lost Battalion.

Fifth Army Commanding Gen. Mark Clark told them,"The whole United States is proud of you."

Not quite. Having survived three major campaigns, T/Sgt. Shig Doi hitchhiked back to Auburn, California. With his duffel bag on his shoulders and a Bronze Star on his chest, the diminutive hero topped the crest of a hill and looked down onto his hometown. Doi still shuts his eyes at the bitter recollection. "Every store on Main Street had a ‘No Japs Wanted' sign out front."

Tule Lake, the last of the concentration camps, closed for good in March 1946. At least a third of all Japanese-American truck farmers on the West Coast found their lands ruined or lost to foreclosure. Japanese neighborhoods everywhere were gone, their rented homes and shops taken over by war workers who had flooded into the region.

Soyo Takahashi found her parents home in Palo Alto filled with migrants sleeping ten in a room. After three wartime years as a cook in an Idaho labor camp, John Saito's mother, Sakuyo, had saved enough money for a down payment on a modest home in southwest Los Angeles; the day she tried to move in, she was handed an injunction, "Restrictive covenant," Saito explains. "A thousand-dollar find and/or a year in jail if we moved in. We sold-for a song."

It has been estimated that Japanese-American losses totaled 400 million dollars-in 1942 dollars. In 1948 Congress appropriated 38 million dollars to settle claims, but the processing was so snarled that the internees settled for an average of a dime on the dollar. Mary Oda's mother, a former teacher who turned to field labor to support herself, carried the ashes of her dead husband, son, and daughter around in an urn for six years, unable to afford a proper funeral. She finally settled for $1,800 just to see them buried.

Some injustices were redressed. In 1952 JACL helped win repeal of California's alien land laws, and Congress granted the Issei's right to citizenship at last. Among those who applied is Michiko Tanaka, now 81. "I have 11 children living and 22grandchildren, all citizens," she said. "I'm entitled."

Social barriers fell too. Nisei men and women found that traditional Japanese values had become marketable commodities in America. "The Japanese work ethic-personal discipline, deference yo authority, high productivity and emphasis on quality-corresponds to the old Protestant ethic," explains UCLA sociology Harry Kitano. "Once these qualities were ridiculed, despised. Now they dovetail with the needs of the American marketplace."

Twenty-five years after the camps were closed, the average personal income of Japanese Americans was 11 percent above the national average; average family income was 32 percent higher. A higher proportion of Japanese Americans were engaged in professional occupations than were whites. By 1981, an astonishing 38 percent of Sansei (third generation) children were attending college, and of these, 92 percent planned professional careers. In California, where more than a third of the nation's 720,000 Japanese Americans reside (88 percent of them U.S. born), family income remains 15 percent above the statewide average. Wrote sociology William Peterson," Even in a country whose patron saint is Horatio Alger, there is no parallel to this success story."

And it's a story told over and over gain. Paul Terasaki, 56, grew up on the poor side of Los Angeles where his father had the ill fortune to open a bakery in 1941. The family spent the war years in the desert camp at Gila River, Arizona. Terasaki worked his way through UCLA, earning a doctorate in immunology-embryology, and studied with Nobel laureate Sir Peter Medawar at University College in London. Today Dr. Terasaki heads UCLA's Terasaki Laboratory, recognized as a pioneer in the crucial area of tissue-matching for organ transplants.

The late Minoru Yamasaki and his bride, Teruko, shared a one-bedroom New York apartment with is parents and younger brother during the war years. Before the war, Yamasaki spent his days boxing imported china; nights, he struggled toward a master's degree in architecture at New York University. The crowning achievement of his career, Manhattan's twin-tower 110-story World Trade Center.

The first Japanese-American astronaut, Lt. Col. Ellison Onizuka of the U.S. Air Force, who died with six other crew members when the space shuttle Challenger exploded last January 28, had dreamed of spaceflight since boyhood. At 13 he had stood on the black lava shores of the Big Island of Hawaii and looked up at the night sky, filled with wonder at the flight of Alan B. Shepard, Jr., America's first man in space. This is how Elli Onizuka described his own flight in 1985:

"I looked down as we passed over Hawaii and thought about all the sacrifices of all the people who helped me along the way. My grandparents, who were contract laborers; my parents, who did without to send me to college; my schoolteachers, coaches and ministers-all the past generations who pulled together to create the present. Different people, different races, different religions-all working toward a common goal, all one family."

Postwar Japanese-American success gave rise to the media catchphrase "model minority." The term makes virtually every Japanese American wince. Some resent being held up for other reaches to emulate. "It's the whites who are the model. We're still the minority," says one San Francisco attorney. "The term measures us against them, on their terms." Others object that the label obscures the many human problems-from neglected elders and broken marriages to kids strung out on drugs-that Japanese Americans share with other Americans.

Many Sansei grew up torn between their parents' unspoken shame and a fierce new American pride in ethnic identity. For a long time, Japanese Americans shrouded the wartime experience from the world, from themselves, and from their own children behind 40 years of silence, a resigned shrug, and the phrase shikata-ga-nai (nothing can be done). "Anger, shame, humiliation-all are part of it," Says Dr. Edward Himeno, a psychiatrist who has worked extensively with Nisei camp victims.

"The Sansei absorbed the emotions their parents bottled up," says Dr. Himeno. "They grew up feeling ‘there's something wrong with me, and I don't know what it is.' " Congressman Robert Smatsui, interned as a one-year-old, offers an illustration. "I remember about age 14 sitting on the back porch with a friend. He said, "Gee, I wish I weren't Japanese." I said, "Yeah, me too."

Some Sansei turned their anger inward. "I did heroin, every drug I could find," relates Vietnam combat veteran Mike Watanabe, now executive director of Los Angeles' Asian American Drug Abuse Program (AADAP); "I wasn't proud of my heritage as an Asian American and wanted to assert my own identify-even if it was a destructive one." Eventually, Watanabe says, he understood that he was proud of being Japanese American. He got off drugs, earned a master's degree, and dedicated himself to social work at AADAP, a storefront community clinic in Los Angeles' multiracial, working-class Crenshaw district. Says Watanabe: "in the ten years I've been here, we're treated thousands of Japanese Americans for drug abuse."

Other Sansei moved to set their ethnic record right. In 1980 five Sansei attorneys crafted a brief laying out the constitutional violations surrounding the camp experience. In 1983 these attorneys and a team of more than 100 volunteer lawyers and law students forced reopening of the three convictions the Supreme Court upheld in 1943 and 1944. In the first of the cases-that of Fred Korematsu, who was tried for resisting internment- a U.S. district court judge in San Francisco cleared the conviction, declaring that our institutions must "protect all citizens from the petty fears and prejudices that are so easily aroused."

The most momentous of the legal actions was finally getting Congress to establish a commission in 1980 to investigate the facts and circumstances surrounding FDR's Executive Order 9066. For the first time Japanese Americans came forward and publicly recounted their experiences in the camps. Men and women wept as they testified. "After 40 years," says Dr. Kuramoto, "the emotional boil was lanced, and the healing process was begun."

After hearing testimony from 750 witnesses, the commission concluded that Executive Order 9066 was not justified by military necessity, that "a grave injustice" had been done to those interned, and that the broad historical causes behind the order were "race prejudice, war hysteria, and a failure of political leadership." The commission recommended the appropriation of 1.5 billion dollars as compensation to the victims. "It was a redemption," says Warren Furutani of UCLA's Asian American Studies Center. "The victims weren't guilty-and the Sansei finally found out what their parents had been through."

Their problem now was to find out who they were themselves. Sansei Philip Gotanda, 35, of San Francisco, perhaps the most prolific of young Japanese-American playwrights, went to live in rural Japan to try to answer the question, "How Japanese am I?" "I had the language down pretty well," he relates. "I was wearing the clothes, getting around fine, feeling comfortable. And one day, walking down the street, I had a profound experience. I suddenly realized that all the faces I'd been seeing in the movies and on television, all the faces of the people on the street, were Japanese. Everyone looked like me. For th first time in my life, I was anonymous."

Gotanda pauses, as if to let the experience sink in anew. "I think it gave me the vantage point to accept the fact that I am not Japanese," he says. "For better or for worse, I am an American."

And what did Gotanda do then?

"I came home," he says with a smile."

Main Index

Japan main page

Japanese-American Internment Camps index page

Japan and World War II index page

|