Men and Women

The play was by H.C. DeMille and David Balasco. Maude Adams played Dora. It's a drama about a bank scandal.

I have found three different opening dates for the play, and the opening theater is different. One source lists it as opening Oct. 21, 1890, and playing until March 28, 1891. This was at Proctor's 23rd Street Theater. A second source listed it as opening on Oct. 31, 1890, and a third source listed it as opening on August 31, 1896. This was at the Empire Theatre. Since that one is five years later, I'm assuming it was either a typographical mistake, or a revival of the original play.

The last source lists the cast as being with Maude Adams playing Dora and Annie Adams, her mother, playing Mrs. Cruikshank, the play being written by Louis N. Parker and Murray Carson. Ethyl Barrymore is also listed as being in the play, doing the character of Priscilla. John Drew, with whom Maude had performed before, playing the part of Jasper.

“Maude's dislike of the part, which obviously suited her personality, probably stemmed from the playwright's denial of her rightful dramatic scenes.” (Maude Adams, an American Idol: True Womanhood Triumphant in the Late-Nineteenth and Early-Twentieth Century Theatre, doctoral thesis, 1984, Eileen Karen Kuehnl)

=====The Bishop of Broadway: the Life & Work of David Belasco by Craig Timberlake; Library Publishers, 1954=====

Belasco and De Mille's charitable but unrealistic view of human frailty found its accustomed place in their final drama, Men and Women, which was produced by Charles Frohman at Proctor's Theater on October 21, 1890. The idea for the play was derived from a contemporary banking scandal, in which the father of a young man charged with embezzlement was reputed to have declared: "I'll save the bank if it costs me a million a day!" This slender theme was nourished with liberal doses of love and family affection and grew into a play of inordinate length. In the course of their collaboration Belasco and De Mille never did learn the importance of sending the critics home early. William Winter bewailed their sparing use of the knife, when heroic surgery was so evidently necessary, and offered this parting comment on their collaboration: "A deplorable lack of brilliant invention has marked most of the previous labors of Mr. De Mille and Mr. Belasco, and even in this play it is difficult to discover evidence of conspicuous originality." The critic of The Herald was resigned to the fact that Belasco and De Mille would wake up one morning and "find themselves rich and ruined -- the successful authors of poor plays." One week later the Dramatic Mirror summed up the case for the critics, finding against the play "that its sentiment is cheap enough, its characters false enough, its comedy vulgar enough, and its construction mechanical enough to meet the requirements of a class that does not know good art from bad art and habitually praises that which deserves condemnation. From which the readers of THE MIRROR will infer that this play is a box office success."

And it was. Like its predecessors, Men and Women enjoyed a long run, remained in the repertory of stock companies until after the turn of the century and ultimately provided grist for the voracious motion picture mills. De Mille and Belasco no doubt found riches and ruin a welcome change from past experience. After Men and Women they parted company amicably because they had little else to say in duo, and Belasco was absorbed in the very special problem of making Mrs. Leslie Carter "an emotional actress." De Mille went on alone to the successful adaptation of The Lost Paradise from the German of Ludwig Fulda. Economist Henry George was his chief inspiration, and the reading of Progress and Poverty prompted The Lost Paradise and converted De Mille and his wife to the "single tax" and other Georgian theories. In 1893 De Mille fell ill while attending the premiere of a Belasco play at the opening of Charles Frohman's Empire Theater. Typhoid fever developed shortly thereafter and he died before his fortieth birthday. Two sons, William C.. and Cecil B.,, collaborated briefly with David Belasco early in their careers before leaving New York to emblazon the name of De Milleacross the flashing night skies of filmdom's capital.

=====The Plays of Henry C. de Mille by Robert Hamilton Ball, David Belasco; Princeton Univ. Pr., 1941=====

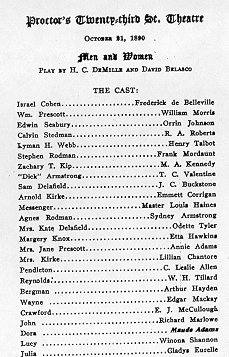

Men and Women, the last play in which De Mille and Belasco collaborated, grew out of a current bank scandal. A young man had speculated with bank funds to which, as an employee, he had access; his father's determination to restore the money, and save the bank and his son received considerable publicity. The title was selected to indicate universal appeal and breadth of theme. To this end also, more sets of lovers than usual are included in the plot. Information for the climactic third act, which was the raison d'tre of the play, came from a friendly cashier. The part of Dora was created for Maude Adams in whom Charles Frohman saw great possibilities. She had briefly appeared for Daniel Frohman as Jessie Deane in Lord Chumley. The part of Mrs. Jane Prescott was written for her mother. The entire cast for the first performance at Proctor's Twenty-third Street Theatre on October 21, 1890, was as follows:

ISRAEL COHEN =FREDERIC DE BELLEVILLE

WILLIAM PRESCOTT=WILLIAM MORRIS

EDWARD SEABURY=ORRIN JOHNSON

MR. PENDLETON=LESLIE ALLEN

MR. REYNOLDS=W. H. TILLARD

MR. BERGMAN=ARTHUR HAYDEN

MR. WAYNE=EDGAR MACKEY

CALVIN STEDMAN=R. A. ROBERTS

LYMAN H. WEBB=HENRY TALBOT

STEPHEN RODMAN=FRANK MORDAUNT

COLONEL ZACHARY T. KIP=M. A. KENNEDY

DR. "DICK" ARMSTRONG=T. C. VALENTINE

SAM DELAFIELD=J. C. BUCKSTONE

ARNOLD KIRKE=EMMETT CORRIGAN

DISTRICT MESSENGER No. 81=MASTER LOUIS HAINES

ROBERTS=A. R. NEWTON

JOHN=RICHARD MARLOW

AGNES RODMAN=SYDNEY ARMSTRONG

DORA=MAUDE ADAMS

MRS. KATE DELAFIELD=ODETTE TYLER

MARGERY KNOX=ETTA HAWKINS

MRS. JANE PRESCOTT=ANNIE ADAMS

MRS. KIRKE=LILLIAN CHANTORE

LUCY=WINONA SHANNON

JULIA=GLADYS EURELLE

If De Mille and Belasco were considered lucky "openers," certainly Men and Women did nothing to vitiate that claim. The play ran two hundred and four consecutive performances, closing on March 28, 1891, and admirably vindicated the prophecies of success made by the reviewers after the dbut. The critic in the Herald , it is true, becoming increasingly annoyed at the obvious similarity between the plays by the collaborators, "the same sugary sentiment, the same hollow pathos, the same forced style," lays about him with considerable vigor. "The first half of the third act, marred though it is by flagrant tricks and absurdities, is unquestionably strong," but otherwise he will have none of it. "The rest of the play is chiefly noticeable for its lack of invention and its deliberate disregard of the laws of stage construction. . . . The dialogue . . . is unreal or trite. There are twice as many people in the play as there should be, and they all talk too much. The plot is involved, and the authors have made the usual blunders of diverting the interest of their audiences from their main story to a host of subsidiary incidents. Lastly their fourth act is superfluous." No, not lastly, for why should a Jew have in his library a stained glass representation of Christ and the Magdalen? Nevertheless, "it will pay, for it appeals to a class of simple-minded playgoers, who will be taken in by its artifice." Some of the basis of this criticism, it is to be noted, was later removed; five or six of the original characters were dropped or telescoped: Congressman Kip, for example, was retired, and became bank examiner, thereby eliminating Lyman H. Webb who had had that function. No doubt other revisions brought further simplification. But except in its estimate of success, the Herald is practically alone in its views. The World thought it "worthy," the Star the "best they have ever written," and the Journal, the Press, and the Commercial Advertiser agreed that it ranked among the best of recent American plays. In the flood of importations, the Times, too, is thankful that "this is a play by American authors, treating of an American subject."

Reviews

“Miss Maude Adams is a pleasing ingenue, and what little she has to do is charmingly done.” New York Times, Oct. 26, 1890.

“A pretty, girlish winsome actress is Maude Adams, whose Dora is a sweet performance that is stamped with a virginal charm.” New York Dramatic Mirror, Nov. 1, 1890

The Standard (Utah), July 12, 1891 |

The New York Times, Oct. 12, 1891 |

The first article is an ad for the play, the second one of the types of articles that spells her name "Maud", leaving out the "e" at the end, but otherwise a nice article.

|