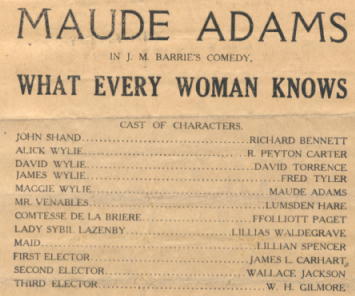

What Every Woman Knows

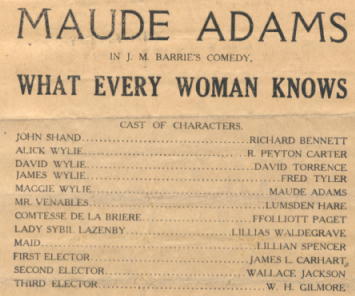

In this four-act play written by James Barrie and produced by Charles Frohman, Maude Adams appeared as the character Maggie. The play opened at the Empire Theater on December 23, 1908 and ran for 198 performances.

Maggie is the wife of John Shand, a Scotch member of the House of Commons.

The show ran for 198 performances. The critics spent most of their time criticizing the play itself. The public, though, liked the play. There was also a special performance on April 19th of 1910. It was a one-day performance at the New Haven Theatre. Money raised went to Yale University Dramatic Society.

The play was also done again during the 1909-1910 season with 25 performances at the Empire Theater.

=====The Theatre Handbook and Digest of Plays edited by Bernard Sobel, 1940=====

"Maggie Shand has played an important part in the success of her husband, John Shand, and in his rise to Parliament. She is now seeing him through an affair with Lady Sybil Lazenby. By giving Lady Sybil enough rope, Maggie wins John back and charts a shred campaign which guarantees his re-election to Parliament. What every woman knows is that she must never allow her man to realize that she is helping him, but must allow him to think that it is his own intelligence and ingenuity that are getting him on."

"The way in which Magie keeps herself in the background, though it is she and she alone who is responsible for her husband's success, is amusingly and cleverly portrayed. "

=====Charles Frohman:" Manager and Man by Issac F. Marcosson and Daniel Frohman, with an Appreciation by James M. Barrie. 1916=====

For over a year Barrie had been at work on a play for her. It came forth in his whimsical satire, "What Every Woman Knows." Afterward, in speaking of this play, he said that he had written it because "there was a Maude Adams in the world." Then he added, "I could see her dancing through every page of my manuscript."

Indeed, "What Every Woman Knows" was really written around Miss Adams. It was a dramatization of the roguish humor and exquisite womanliness that are her peculiar gifts.

As Maggie Wylie she created a character that was a worthy colleague of Lady Babbie. Here she had opportunity for her wide range of gifts. The role opposite her, that of John Shand the poor Scotch boy who literally stole knowledge, was extraordinarily interesting. As most people may recall, the play involves the marriage between Maggie and John, according to an agreement entered into between the girl's brothers and the boy. The brothers agree to educate him, and in return he weds the sister. Maggie becomes John's inspiration, although he refuses to realize or admit it. He is absolutely without humor. He things the can do without her, only to find when it is almost too late that she has been the very prop of his success.

At the end of this play Maggie finally makes her husband laugh when she tells him:

"I tell you what every woman knows; That Eve wasn't made form the rib of Adam, but from his funny-bone."

This speech had a wide vogue and was quoted everywhere.

Curiously enough, in "What Every Woman Knows" Miss Adams has a speech in which she unconsciously defines the one peculiar and elusive gift which gives her such rare distinction. In the play she is supposed to be the girl "who has no charm." In reality she is all charm. but in discussing this quality with her brothers she makes the statement:

"Charm is the bloom upon a woman. If you have it you don't have to have anything else. If you haven't it, all else won't do you any good.

"What Every Woman Knows" was an enormous success, in which Richard bennet, who played John Shand, shared honors with the star.

=====The Theatre Handbook: And Digest of Plays by George Freedley, Bernard Sobel; Crown Publishers, 1940=====

Maggie Shand has played an important part in the success of her husband, John Shand, and in his rise to Parliament. She is now seeing him through an affair with Lady Sybil Lazenby. By giving Lady Sybil enough rope, Maggie wins John back, and charts a shrewd campaign which guarantees his re-election to Parliament.

What every woman knows is that she must never allow her man to realize that she is helping him, but must allow him to think that it is his own intelligence and ingenuity that are getting him on.

The way in which Maggie keeps herself in the background, though it is she and she alone who is responsible for her husband's success, is amusingly and cleverly portrayed.

=====Theatre U.S.A., 1665 to 1957 by Barnard Hewitt; McGraw-Hill, 1959=====

Mr. Barrie is delightful with his whimsicalities, and we may always be sure that any new play from him will be filled with droll fancies, true observations of character and delightful touches of nature. The absence of all trace of conventionality in his plays is also a source of pleasure. . . .

The charm of his comedy, " What Every Woman Knows," is largely in its minute detail, which involves truths of life and character expressed with whimsical humor. What could be more unpromising to the ordinary, conventional dramatist than the idea of three bachelor brothers agreeing to educate an egotistical, ambitious young Scotchman and willing to sign a contract to that effect, if only he will marry their spinster sister, age 27, if after three years she is still free? What could be more whimsical than to have this young man, who knows that the brothers retire to bed promptly at ten and sleep soundly, and intent upon educating himself, steal into the library where there are ten yards of books which are never read by the household, and spend the night in devouring them. The three brothers and the maiden sister have reason to suspect that the house is being entered, and they determine to surprise the mysterious visitor. The young man enters through the window, gets his book and is completely absorbed in it as they tip-toe in, the spinster carrying a poker. There is no describing in detail the delightful scene which follows. The canny young Scotchman drives his enforced bargain with a wariness which is characteristic of the race which Barrie knows so well and with an unconscious humor which keeps the audience in a constant state of pleasurable appreciation of every moment of the scene. The spinster is canny, too, and her manner of receiving the proposition is delicious comedy.

The young man succeeds in life and is elected to Parliament. The spinster feels that he doesn't love her and is willing to tear up the agreement, but he insists that a bargain's a bargain and they are married. His success continues, there is a chance of his entering the Cabinet. Maggie has helped him in his speeches, which have made him eminent, more than he knows, but he is frankness itself. He tells the three brothers and his wife that he is in love with another girl of title. A divorce is decided upon. In the later developments of the play, however --after Maggie, rejected by him, saves the day for him at a critical moment in his political career--he discovers that he does not love the aristocratic girl after all and he tells her in the presence of the other characters that she bores him, while the lady of title confesses that he likewise bores her. There is then a scene between him and the neglected Maggie, in which they talk over matters and in which she makes him laugh for the first time in his life. He now understands her and realizes that she is the companion made for him. The whimsical idea is that she is his missing funny bone and that woman was not made from the rib of man at all. This sounds nonsensical, but the play is wholly delightful. Richard Bennett as John Shand proves himself an actor of the very finest intelligence. His John Shand is a rare achievement. There is hardly any rle in the acted drama that is beyond this young player's capabilities. Maude Adams as Maggie Wylie, the spinster, exercises her potent and almost indescribable charm of personality and art. What the effect would be if the part were played by an actress less lovable it would be curious to conjecture. As it is, the whimsical conditions of the play, with reference to her share in the action, seem to be susceptible of better interpretation by Miss Adams than by any other actress on our stage. Without her spirituality the situation of a spinster of 27 regarding a young man as her boy, and loving him and marrying him, might have a grossness entirely out of keeping with the gentle refinement of the character and play. If one may be permitted to criticise any part of an impersonation that was wholly satisfying and delightful, it is that Miss Adams makes too charming a Maggie. The logic of the plot calls for a homelier heroine. It is impossible to conceive that John Shand, no matter how egotistical, could be so blind to the worth of the gentle creature who was the Svengali of his success.

=====Scotland in Film by Forsyth Hardy; Edinburgh University Press, 1990=====

The theme of What Every Woman Knows -- that behind every successful man is a woman more perceptive and with greater resources -- has a certain universality. Barrie's particular illustration of it took the form of a bargain made by the family of a supposedly unattractive young woman that she shall legally marry a young man with political ambitions who, when he is successful in Parliament, fails to realise the source of his success. In its essentials the film was faithful to the original, although the four-act structure of the stage version was broken up to provide the film with greater variety in its background. In the part created by Maude Adams, Helen Hayes gave an appealing performance and Brian Aheame was the ambitious politician, blind to his wife's qualities. David Torrence as the father and Donald Crisp and Dudley Digges helped, as they invariably did, to sustain the illusion of a Scottish setting.

=====Curtain Time: The Story of the American Theater Book by Lloyd Morris; Random House, 1953=====

After meeting a poor reception in Washington during a tryout engagement, Miss Adams brought The Little Minister to the Empire on September 30, 1897. This date was, in a sense, historic. It marked the inception of that amazing relationship between the American public and the star which, beginning as a onesided love affair, developed into a worship without precedent or subsequent parallel. Miss Adams was twenty-five, winsome rather than pretty, slight, frail and girlish. Her lilting speech and muted laughter, the delicacy of her tread, the graceful swiftness of her movement, gave her a quality that soon was described as "otherworldly." Though intensely feminine, she made a curious impression of elusiveness, as if she had an elfin strain. A decade later Barrie was to say of a play that he had written for her, "I could see her dancing through every page of my manuscript." In that play, What Every Woman Knows, he gave her lines which defined her appeal for him, and certainly for the public: "Charm is the bloom upon a woman. If you have it, you don't have to have anything else. If you haven't it, all else won't do you any good."

=====Essays on Modern Dramatists by William Lyon Phelps; Books for Libraries Press, 1921=====

For sheer audacity, it would be difficult to parallel the opening of What Every Woman Knows ( 1908). The curtain rises and not a word is spoken for seven minutes. To conceive and to insist on such a situation is an indication of how much confidence the playwright had in himself, and in his audience. His confidence was justified, though it would be foolhardy for another to imitate it. I remember hearing of one play, where the curtain rose on an empty room; a dim lamp was burning; a woman in black entered, took a seat at the table, and gave vent to a long sigh. Some one in the gallery said kindly, "Well, don't let us keep you up," and the audience went into such hysteria that the play could not go on.

In the beginning of this play, one sees that the author's silences are as impressive as his dialogue--in fact, it is dialogue, a kind of song without words. Silence is used for comedy, as Maeterlinck uses it for tragedy. The two men at the dambrod, the alternation of triumph and despair, were greeted by the audience with every indication of joyful recognition; and at the pat moment, in walks David, and removes his boots. You can hear the clock ticking, and when the silence is finally broken by David's voice, not one guess in a million would have predicted what the granite-like Scot would say -- it is a quotation from Tennyson Maud!

This is one of the masterpieces, in the same class with The Admirable Crichton and Dear Brutus. The construction of the piece is as near perfection as the human mind can make it; the unexpected happens in every scene, just as it does in history. The surface caprices and quiddities of human nature are all accurately charted, and the depths of passion--love, jealousy, ambition--are revealed. If the dramatist had written only this play, we should know that he was a man of genius. No amount of toil can turn out work like this; it is sheer revelation; it is, as Turgenev wrote to Tolstoi, a gift coming from that source whence comes all things.

The scene in the third act is a scene of tremendous passion--the air is tense with it; and yet, with keen excitement, there is not even a penumbra of melodrama. It is as though the suffering were so intense and terrible that we can have no smell of the theatre in these flames; that we can have only reality, too harsh and bitter--and too infinitely tender--for any play-acting. Then we suddenly remember, after the scene is over, that it was "only a play." Just that: "only a play"-only a great work of art, only a profound revelation of the evil and of the sublimity hidden in every man and woman.

Here is a decisive battle between love and lust--between the grace of God and the power of the world. Maggie says to her brother, "I'll save him, David, if I can.""Does he deserve to be saved after the way he has treated you?""You stupid David. What has that to do with it?"

In the published version, two passages are omitted, both of which made a palpable hit in the theatre. I do not know why Mr. Barrie cancelled them, but it is fair to guess. The first is in the great scene in the third act: Maggie's father and two brothers pass by the self-condemned and yet defiant John Shand: every one of the three brands him with a monosyllabic epithet; I remember only the third. Let us suppose the first man hissed "Scoundrel!" the second, "Traitor!" now the third, with terrific emphasis shouted "ENGLISHMAN!" At the London performance, this word drew more delighted laughter and applause than any other speech. Is it not possible that in some ways the English have a more acute sense of humour than the Irish? This speech is one of Mr. Barrie's greatest audacities, but he knew his audience; he foresaw the result. Suppose a similar scene was presented with the Scotsman shouting Irishman! He would be mobbed.

Perhaps in print the author could not be sure that the reader would hear the proper tone of the voice, nor that he would understand it. Furthermore, the play was published during the dark hours of the war, and he could not bring himself to say that word in that way, even in jest. This, anyhow, is my guess; but I am sorry for every one who did not hear the original version.

The other omission is just before the click of the final curtain. This is what happened in the theatre. "Oh, John, if I could only make you laugh at me!""I can't laugh, and yet I think you are the drollest thing in all creation.""We're all droll to them that understand us, and I'll tell you why; Eve wasn't made out of Adam's rib; she was made out of his funnybone." Now I think the reason why he left this out is because it is not good enough; it is good enough for most dramatists; it would make the fortune of some; but it is not good enough for J. M. Barrie. In my opinion, the printed version gains by its omission.

Oh, John, if only you could laugh at me."

"I can't laugh, Maggie."

(But as he continues to stare at her a strange disorder appears in his face. MAGGIE feels that it is to be now or never.)

"Laugh, John, laugh. Watch me; see how easy it is."

(A terrible struggle is taking place within him. He creaks. Something that may be mirth forces a passage, at first painfully, no more joy in it than in the discoloured water from a spring that has long been dry. Soon, however, he laughs loud and long. The spring water is becoming clear. MAGGIE claps her hands. He is saved.)

Never shall I forget that Monday afternoon in the spring of 1909 when Maude Adams presented this play in New Haven. She presented it in every sense of the word, making an outright gift of the gross receipts to the Yale University Dramatic Association. She hired the theatre, paid the salaries of the actors, paid for the transportation of the company and the scenery from New York and return, so that every cent taken was given to the beneficiary. The performance began at one o'clock, as the play had to fill its regular date in New York at eight. The theatre was jammed; and the special occasion put both actors and audience on edge. There was a tenseness in the atmosphere that it is impossible to describe--the actress and her company fairly outdid themselves, and everyone in the house, from President to sweep, was melted --I remember one grey-bearded professor sitting near me, who, as the tears coursed down his whiskers, exclaimed, "I thought you said this was a comedy!" It was impossible to restrain one's emotion; and that it reacted on the stage may be surmised from the fact that in the last scene both Miss Adams and the leading man were so overcome that they could scarcely articulate. After a score of recalls, an undergraduate, representing the Dramatic Association, stepped on the stage, announced that Maude Adams had been made an honourary member, and presented a medal. She was both laughing and crying, and it seemed impossible that she could make a speech. But she did. She surprised us even as Maggie surprised John Shand at the end of the second act. With an affectionate gesture that embraced the audience she said:

My Constituents!

It seemed incredible that the third act could be anything but an anticlimax; but there is no surer proof of Barrie's genius than his last acts, the final test of constructive power. I will go so far as to say that even in most successful plays, the last act is either a downright failure or at best a falling away. But in Dear Brutus, as in The Admirable Crichton, in What Every Woman Knows, and in all Barrie's plays, the last act crowns the work.

=====The Twentieth Century Theatre: Observations on the Contemporary English and American Stage by William Lyon Phelps; The Macmillan Company, 1918=====

Suppose some Briton writes a first-class play; I suppose a Briton, because he is more likely to perform such a public service than an American. Let us take a fine example -- What Every Woman Knows, by J. M. Barrie. This is a drama full of thought, full of action, full of charm -- a great play. Every city and town in the United States ought to have the opportunity of seeing and hearing it, and it would be an enormous gain if we could all see and hear it at the same time. What are the terms by which an American may be permitted to witness it at all? It is produced at one theatre in one town by one company. The management hopes that it will run there at least a year. During that year if any person in Cleveland or Buffalo or St. Louis or Chicago or Salt Lake City happens to want to hear this drama performed, he must journey to New York, and succeed in the endeavour to buy a seat at the particular building where it is being produced. After the lapse of a year, or perhaps two or three years, it may be taken on the road, and it may or may not come within the range of the people living in the towns I have mentioned. Americans endure this situation in dramatic art without a protest; whereas if the case in question were some physical luxury, they would not endure it for a moment.

In some European countries, when a new play is produced in one of the large cities and the thing is successful, within a week every other city and many of the small towns are enjoying the same piece. This means that everybody in the country is talking about the same play at the same time -discussing it, arguing about it, reading criticisms of it in the local papers. The new play is an educational force; it is really a part of the national life. Europeans have often the same curiosity in dramatic art that we have in mechanical inventions, devices to lower expenses and increase profits, or a new system of dieting. A significant play in Europe is discussed with something of the same general eagerness that Americans talked about the book Eat and Grow Thin. It is a national sensation.

Now Americans by nature are not one whit more materialistic than Europeans. We simply are not informed as to what ought to be the condition of dramatic art. I am certain that if we had the opportunity we should take advantage of it. There is an immense amount of intellectual and spiritual hunger in America. The so-called "practical" and shrewd theatre-managers who are the shepherds of our souls have a lower opinion of our intelligence than the facts warrant. Over and over again they decline to give us good music and good drama, because they are so cocksure we do not want it. When John Galsworthy's new play Justice was brought to America it was offered in turn to a succession of dramatic managers, who contemptuously rejected it. The American people will never stand for that high-brow stuff." Finally one person was found who was willing to risk the venture. To the amazement of the "practical" men the play turned out to be an enormous financial success; night after night the house was crowded.

=====American Theatre: A Chronicle of Comedy and Drama, 1869-1914 by Gerald Bordman; Oxford University Press, 1994=====

December's biggest hit was a Charles Frohman importation, James M. Barrie's What Every Woman Knows ( 12-23-08, Empire). With Maude Adams, Broadway's most charming and popular actress, as Maggie Shand preaching Barrie's thesis on the potency of charm and secretly helping her ridiculously conceited husband climb the political ladder, it was hailed, appropriately, as "one of his most engagingly whimsical and insistently charming works." The comedy packed in audiences for six months. The rising Richard Bennett played Maggie's husband, John.

=====Guide to Great Plays by Joseph T. Shipley; Public Affairs Press, 1956=====

James M. Barrie

In life's intertangling of the sexes, Bernard Shaw saw woman as the huntress, love being but a disguise for the "life-force" that must find continuance; Barrie, on the other hand, emphasized the tender and tolerant, protective mother-feeling of a loving wife. Barrie's attitude was most fully developed in What Every Woman Knows.

When John Shand breaks into the Wylie house in this play, he does so in search of learning, not money. The Wylies have the best library in their little Scotch town. They also have the unmarried Maggie. Catching John in unlawful entry, the Wylies bargain with him: they will put him through law school if he will marry Maggie. The bargain kept, Shand goes on to Parliament, becoming a popular leader. When he is attracted to Lady Sybil Lazenby while Maggie is away from him, Shand discovers how much his success has hinged upon Maggie, whose sense of humor gives sparkle to the ideas of her intelligent and hard-working but humorless husband. Shand manages to see the irony and humor of the situation, and the way is cleared for the happiness of John and Maggie.

What Every Woman Knows opened in London in September 1908, with Hilda Trevelyan ( Maggie), Gerald du Maurier (John), Lillah McCarthy, Edmund Gwenn, and Mrs. Beerbohm Tree. It was an immediate success. The play came as a Christmas present to Broadway on December 23, 1908, with Maude Adams and Richard Bennett. It has since been continuously popular. Maggie has been played by Helen Hayes ( 1926, 1938); Frances Starr ( 1931); Pauline Lord ( 1931); and Muriel Kirkland ( 1942). In 1946 the American Repertory Theatre revived the play, with June Duprez ( Maggie), Richard Waring (John), Ernest Truex, Philip Bourneuf, Walter Hampden, and Eva Le Gallienne. It was filmed in 1921 with Lois Wilson and Conrad Nagel, and again in 1934.

Of the Broadway premiere, The New York Dramatic Mirror ( January 2, 1909) commented: "What every woman knows is that Eve was made not from Adam's rib but from his funny-bone . . . Perhaps it is not his best play, but it is as good as any of the others, no matter how paradoxical that may sound. And the role of Maggie was made for Maude Adams."

Critics have expressed curious ideas as to Barrie's intent in writing What Every Woman Knows. Freedley and Reeves said in A History of the Theatre ( 1941): "The thesis that every prominent man is a fool and that an intelligent wife must struggle to prevent his learning it, is distinctly depressing." (Freedley apologized in part by calling the play, after the 1946 revival, "the most delightful Scottish comedy of them all.") And Alexander Woollcott ( April 14, 1926) said that the play was written "in support of Barrie's favorite conviction that all women have the wisdom of the serpent and that all men are but lummoxes." As a matter of fact, John Shand is both hard working and intelligent; he has both ambition and drive, together with a recognition of his potentialities. What he lacks is a sense of humor, the ability to stand off and look and laugh at himself -- which Maggie manages to supply. That a woman can twist a man around her little finger is another matter, and, as Shaw and Barrie agree, a common masculine susceptibility.

There abide in What Every Woman Knows the quintessential qualities of Barrie. It has satire, "tenderized" by humor; it has charm, and the author's love of life; it has understanding without malice, understanding that humbles a man without lessening his dignity; it has a rippling and ripening of character; and it has a swift and easy flow of plot. The Wylies in the play are alarmed at what a Scot may do with 300 of education; Barrie shows what a mind of understanding and a heart of love can do -- which is indeed what every woman knows.

Reviews

Again, the critics praised her work:

"There is human nature, there are heart throbs, and there is more than one laugh with a tear in the middle...Miss Adams was admirable in the role of Maggie......Her best work was noticed in the scenes of suppressed agony of spirit and the philosophic tone of her gentle martyrdom."

She also performed the play on April 19, 1909 for a special performance for the Building Fund of the Yale Theatre. A rather lengthy analysis ran like this:

"Never shall I forget that Monday afternoon in the spring of 1909 when Maude Adams presented this play in New Haven. She presented it in every sense of the word; making an outright gift of the gross receipts to the Yale University Dramatic Association. She hired the theatre, paid the salaries of the actors, paid for the transportation of the company and the scenery from New York and return, so that every cent taken was given to the beneficiary. The performance began at eleven 1l o' clock, as the play had to fill its regular date in New York at eight. The theatre was jammed; and the special occasion put both actors and audience on edge. There was tenseness in the atmosphere that it is impossible to describe-the actress and her company fairly out-did themselves, and everyone in the house, from President to sweep, was melted-I remember one grey-bearded professor standing near me, who as the tears coursed down his whiskers, exclaimed: 'I thought you said this was a comedy!' After a score of recalls, an undergraduate, representing the Dramatic Association, stepped on the stage, announced that Maude Adams had been made an honorary member, and presented a medal. She was both laughing and crying, and it seemed impossible that she could make a speech. But she did. With an affectionate gesture that embraced the audience she said:"

"My Constituents!"

"But she seemed for a part of the time to be laboring under a great nervous strain, and her identification with the role was not so complete as might have been desired. In the first two acts especially she seemed overwrought almost to the point of hysteria, and the suggestion of character in speech and action was lacking."New York Times, Dec. 24, 1908

"Perhaps she would better fit Mr. Barrier's conception of his heroine if she could make herself less charming; Maggie's attraction lay in the funny0-bone rather than in the bloom."The Outlook, Jan. 9, 1909

"If one may be permitted to criticize any part of an impersonation that was wholly satisfying and delightful, it is that Miss Adams makes too charming a Maggie. The logic of the plot calls for a homelier heroine. It is impossible to conceive that John Shand, no matter how egotistical, could be so blind to the worth of the gentle creature who was the Svengali of his success."The Theatre, Feb. 1909

"In the opening act of 'What Every Woman Knows,' for example, Miss Maude Adams, most popular of players, acts very badly. She strives by every little trick at her command to be charming; and the part distinctly calls for a complete absence of charm. Awareness of Maggie's charm should come gradually, not only to John Shand, but to the audience. A large conception of the role of Maggie, which saw it firmly in relation to the entire play, would bring about quite a different impersonation and a better one. ...But Miss Adams has a witchery about her which makes it doubly difficult to visualize a character she is playing apart from her impersonation. It is doubly difficult to convict her of error before the jury of the public. American Magazine, July 1910

The play was received with many curtain calls and Miss Adams, visibly moved by her enthusiastic greeting, barely managed to stammer out her thanks."New York Sun, Dec. 24, 1908

"Miss Adams was most enthusiastically greeted after each act, and once she came forward and thanked the Yale men for inviting her to appear here. As the curtain fell on the last act the entire audience arose and cheered. The ascending curtain then showed that great masses of flowers, in which violets were conspicuous, had been rushed in from the wings, the gifts of many friends. Max Perry, president of the Dramatic Association, stepped out of a box and, addressing Miss Adams, announced her election as an honorary member, and he presented her with the medal of the association. then from the footlights Mr. Perry led Yale men in the long cheer, with three "Maude Adams,"and as this died away the Glee Club sang 'For God, Our Country, and Yale."Miss Adams thanked the audience, and for several minutes there was cheering."New York Times, April 20, 1909

Ad for the Play

The Syracuse Herald, Dec. 18, 1908 |

The Washington Post, Jan. 3, 1909 |

Trenton Eventing Times, Jan. 13, 1909 |

The Nebraska State Journal, Jan. 17, 1909 |

The Nebraska State Journal, April 16, 1909 |

Note in the article on the right that then-president William Howard Taft saw a Maude Adams play, making several Presidents that saw her plays.

The Nebraska State Journal, April 18, 1909 |

The Washington Post, Dec. 5, 1909 |

The Lima Daily News, Dec. 13, 1909 |

The Lima Daily News, Jan. 16, 1910 |

Last article: This is one of the very few things I've found which has anything to do with the politics of the time. Remember that, during this time in the U.S., women were working hard to get the right to vote. Yes, if you didn't know it, women in the U.S. were not allowed to vote (with the exception of a few states) until 1920, and the women who led the movement to get the right to vote often ran afoul of the law. They were subject to intimidation, arrest and even beatings.

The Indianapolis Star, March 21, 1910 |

Colorado Springs Gazette, May 3, 1910 |

The Daily Review, Nov. 14, 1910 |

The book of the play and other material can be found here.

|